MacKenzie “Mack” Miller was not a steeplechase trainer, but he certainly had connections to jump racing through Aiken, S.C., where he wintered over several decades of his Hall of Fame career. Miller once owned the steeplechase race course where the Aiken Steeplechase has been held for many years.

As he told Audrey Korotkin in 1991, he had two principal goals. He wanted to win Saratoga Race Course’s Travers Stakes (Gr. 1), and he accomplished that goal in 1987 with Paul Mellon’s Java Gold. A son of the Blue Grass, he also wanted to win the Kentucky Derby (Gr. 1), but that goal had eluded him at the time the following chapter of unpublished Great Trainers of the Twentieth Century was written. He checked that box two years later with Mellon’s homebred Sea Hero, a half-brother to Hero’s Honor. Sea Hero, by Polish Navy out of Glowing Tribute, also won the 1993 Travers.

Mack Miller retired from training in 1995 and died on Dec. 10, 2010, at the age of 89. His wife, Martha McCauley Miller, died March 22, 2015, at the age of 91.

MacKenzie Miller: An Aiken icon

by Audrey R. Korotkin

It was mid‑March in 1991, and the first intimations of spring’s approaching warmth whispered through the ancient pines of Aiken, South Carolina, a lovely, sedate Victorian community where the Thoroughbred has been king for much of the 20th century. MacKenzie Miller, a winter resident of Aiken for more than 30 years, settled his narrow, 6‑foot‑2 frame into the desk chair and leaned back as he spoke on the telephone.

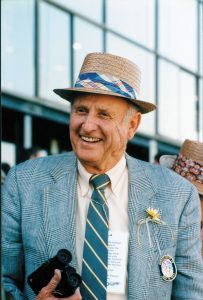

Mack Miller at the Preakness Stakes in 1993. ©Anne M. Eberhardt

Surrounding him in his stable office were warmly paneled walls filled with winner’s circle photos from years past, remembrances of the outstanding horses and the outstanding owners with whom he has been associated. As he spoke, his eyes wandered toward the office’s screen door, looking for the next set of two‑year‑olds heading for the training track. On the other end of the phone line, an employee of Paul Mellon’s Rokeby Farm in Upperville, Virginia, was briefing Miller on the past day’s events. As Mellon’s private trainer for 15 years, Miller also was responsible for the development of the young horses back on the farm.

Past, present, and future: All of them had their place as Mack Miller prepared for the 1991 racing season. In a few short weeks, he and his crew would depart Aiken’s gentle mornings and ship to New York. But here in Aiken, which is separated from New York by more than miles, Mack Miller was in his true element. It has a history, a pace, and a style of life that ideally suit the man. “The people here have always been true Southern ladies and gentlemen, and that means an awful lot, having been in New York,” he said.

Indeed, Miller has been in New York, has trained successfully there for decades, has scored many of his principal triumphs there. Whether they ran at Saratoga or Belmont Park or Atlantic City Race Course (horses that he trained won six runnings of the United Nations Handicap [G1], subsequently renamed the Caesars International Handicap [G2]), all of them trained at Belmont after spending the winter at Aiken.

From Leallah, his first champion in 1956, through championship‑caliber Java Gold in 1987, the horses trained by Miller have won many of New York’s most prestigious races. His three grass champions‑‑Assagai (1966), *Hawaii (1969), and *Snow Knight (1975)‑‑all won the Man o’ War Stakes, as did Dance of Life in 1986. Wearing the colors of Mellon’s Rokeby Stable, Fit to Fight became only the third horse to sweep the New York handicap triple‑‑the Metropolitan (G1), the Suburban (G1), and the Brooklyn (G1) Handicaps‑‑in 1984.

Winter’s Tale, one of the trainer’s favorites, won the 1980 Suburban, Brooklyn, and the Marlboro Cup Invitational Handicap (G1). Among Miller’s stellar grass runners were Hero’s Honor, Tentam, and Halo. Java Gold, who had the misfortune to come along in the same year as Alysheba, defeated the 1987 Kentucky Derby (G1) winner in the Travers Stakes (G1) and also won that year’s Marlboro. Because of the quality of the horses and the quality of the man, MacKenzie Miller was inducted into the National Museum of Racing’s Hall of Fame in 1987.

Miller has moved in the top ranks of Thoroughbred racing for so long that it is easy to forget that‑‑although born in Kentucky’s Bluegrass‑‑horses were not directly a part of his family background. His prospects in the business were so unpromising immediately after World War II that he had difficulty finding even the most lowly of jobs on Lexington’s horse farms. He and his wife, Martha, also spent many lean years before he joined forces with Charles Engelhard in 1961. Miller also has trained for E. P. Taylor and Jane Goodwin, but he has principally trained for two clients‑‑Engelhard and Mellon‑‑over more than three decades. “I guess I’ve been blessed with good luck, to have worked for two giants of the Turf and two men of this great quality,” he said. “It’s a miracle it happened.”

The main barn at Aiken ©Barry Bornstein

Engelhard also was responsible for Mack Miller’s surroundings in Aiken. The training complex, with its comfortable office, sunny stalls, and easy access to the Aiken training track, was built by Engelhard to Miller’s specifications. No wonder Mack Miller seemed so much at home there.

Home was, in fact, Versailles, Kentucky, where MacKenzie Miller was born on October 16, 1921. His father, Scott Miller, was a maintenance supervisor in Lexington for a company that ultimately became the Greyhound bus lines. His mother, Jane Arnold Miller, “was a marvelous lady,” Miller recalled. “She was extremely kind and worked hard to help feed and clothe us. In the community of Versailles, she was always looked upon as one of the really fine ladies‑‑everybody loved her. So I was happy to be able to help take care of her when my father died.” Jane Miller lived to be 93‑years‑old, “and I hope I’ve got her genes,” her son said.

Scott Miller, who also had operated a failed Studebaker dealership, first sparked his son’s interest in horses and racing. “My father had no money, but he had a great love for horses, and I don’t know where he got it. When I was a kid, he had some equity in some racehorse around Kentucky‑‑which he couldn’t afford‑‑or some equity in a broodmare.” Miller recalled being exposed to the Daily Racing Form at an early age, and the publication fascinated him from the start.

For Miller, the greatest thrill of his adolescence was going to Keeneland Race Course’s inaugural race meeting in October 1936, when he was just 15. “I appreciated so much the opportunity to see those beautiful animals, and the following day, my father took me out to see the horses work in the morning.”

As he grew older, Miller went to the races just for fun, with no thought of making it his career. He was too busy working other jobs to bring in money for the family, which also included an older brother, Scott, and a younger brother, Mason. Even if he had thought about working at the track, his father most likely would have put his foot down. He had other plans for his middle son.

“My father wanted us to have an education. My last two years of high school, I went to prep school in Jacksonville, Florida. It was actually a military school,” Miller said. In the fall of 1941, Miller enrolled in the University of Kentucky, but he enlisted in the Air Force following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7. It was not, however, the military career that he had envisioned. “I joined the Air Force as a cadet and was called up the following May or June. But I washed out of flying because my depth perception was not good‑‑at least that’s what they told me. And when you wash out, you revert back to a private.”

Miller was assigned to Forth Worth Air Field, where he became a printer because that was the first job he was able to find. So, after his four‑year stint, his only training was in how to operate printing equipment. Although he did not appreciate it at the time, Miller also had learned regimentation and how to keep accurate notes and records. It was a skill that would serve him well later when records of training, workouts, and medication would become important. After the war, he returned to the University of Kentucky and was “absolutely miserable.” He informed his father he was not meant to be a student‑‑that he had decided to go into the horse business.

That was, however, easier said than done. Unlike so many of his Bluegrass‑raised contemporaries‑‑ Woody Stephens, for example‑‑Miller did not know the first thing about working with horses. Still, he made the rounds on the hope that somebody would give him a chance. “I went all over Central Kentucky, starting at Calumet. I said: `I don’t know a horse from a goat. But I want to learn the business from the bottom up.’ And they turned me down. I went to C. V. Whitney, to Jock Whitney‑‑to the most fashionable farms. And everybody turned me down.”

In despair, Miller went back to Paul Ebelhart, Calumet’s manager, and told him: “I’m going to try this thing, and I’m going to be at work in the morning. You don’t have to pay me, but I’ve got to get this out of my system.” With some encouragement from Margaret Glass, a Calumet office secretary who had worked with Scott Miller at the bus company, Ebelhart gave Miller a job working with broodmares for $125 a month.

At Saratoga in 1990 ©Barbara Livingston

The work was hard and the hours long‑‑13 days on, one day off. Miller progressed to the training stable, where he broke yearlings. But an act of nature‑‑and some professional jealousy‑‑soon ended his career at Calumet. “It was a windy day in December, and there was a storm brewing. We were out in the field with a bunch of colts that had been weaned, and they wouldn’t stop. We corralled them into a corner, another fellow and I, and we were waving our hands to contain them. And Bob Moore was in charge of the yearlings then. And we got back to the gate to put these in, and Bob said to me: `You’re fired.’ And I said: `For what?’ And he said: `You were throwing shanks at the horses.’ And I said: `No, I’m sorry, you’re wrong. I did have a shank in my hand, and we were trying to contain them.’ He said: `Go the office and get your check.’ So I got fired.” He was told later by another Calumet employee that Moore had wanted to get rid of him because he feared Miller would take his job. His firing had been, in fact, a backhanded testament to the progress that Miller had made in a very brief time.

The next few years were lean ones for Mack Miller, now a licensed trainer. In the winter of 1948, he went to work for K. S. “Kurt” Cleveland, a friend of his father’s for whom he helped to break and train the second‑string horses for cotton magnate C. C. Boshamer in Clover, South Carolina. Boshamer staged a private competition the following spring, and Miller’s charges, the scrubs of the pack, performed better than those of the first‑string trainer, Ned Gaines. When Boshamer rewarded the effort by giving their horses to Gaines, Cleveland and Miller promptly resigned.

Miller hustled around Kentucky and River Downs in Ohio for a year or so, notching his first victory as a trainer with Shifty Dora at Churchill Downs in 1950. He then spent two years in Chicago, but none of his horses were runners. He finally decided it was time to stop training for one person at a time and opened a public stable. He was able to scratch out a living by training horses for Central Kentucky breeders such as Ned Brent, Charlton Clay, and the Nuckols family. Newly married to the former Martha McCauley from his hometown of Versailles, Miller journeyed to New Jersey in 1952, where he fell in love with Monmouth Park. With compatriots like Elliott Burch and Jim Maloney nearby, it was a time of great joy for Miller‑‑a period that quickly came to an end.

“Johnny Clark (a well‑known Lexington bloodstock agent and trainer) asked me to take a private job with Saxon Stable. And I did. And it lasted exactly ten months,” said Miller, whose first experience as a private trainer left him bitter. “It was kind of a slap in the face. The horses I had inherited from the previous trainer were pretty well broke down. I think I won three races at Santa Anita in ’53 and ’54, and I thought I was flying, because I didn’t have much to work with. But I was young, and I’m quite aware of that.”

Saxon’s owners fired Miller after he had traveled to New York for the spring 1954 racing season, and he could not find steady work until he returned to Kentucky in July. He once again set up a public stable‑‑and he once again made the rounds of the Central Kentucky breeding establishments in an effort to round up clients. It was a tough sell. “First of all, you had to rely on somebody you knew who was connected with the business to give you a break,” Miller said. “And I got some help from people. Then you have to win a race or two. And if you win enough, other people will sort of migrate to you.”

Miller started with a filly purchased out of a horses‑in‑training sale at Saratoga by R. Smiser West, who remained a close friend and partner through his career. “Her name was Best Side, and he bought her for a broodmare‑‑she couldn’t run,” Miller recalled. “And I said: `I’m going to put that filly into training, because I think she can win in Kentucky, where she can’t win in New York.’ I ran her at Keeneland that fall, and she was second. I took her to Louisville, and she won. I think she won a total of about $2,500. And that was my training bill‑‑he gave me all the money she’d won.”

Slowly, Miller picked up Lexington‑area clients, most of whom sent him fillies that had been retained for breeding. His clients included Dr. Eslie Asbury, Charlton Clay, and Mrs. Jane Goodwin, for whom he turned the filly Oil Painting from a non‑performer into a stakes performer. By the spring of 1955, Miller had eight or nine horses‑‑enough to take to Jamaica Racecourse in New York.

Although he won some stakes races, including Aqueduct’s Distaff Handicap and Belmont’s Maskette Handicap with Oil Painting, the first year in New York was a struggle. In his second year in New York, though, Miller developed Charlton Clay’s Leallah into the champion two‑year‑old filly. Bred by Clay at his Marchmont Farm near Paris, Kentucky, the *Nasrullah filly out of Lea Lark, by Bull Lea, sustained only one defeat in her eight starts that year, and that loss was over a Washington Park track rated as heavy.

Within 30 days in June and July, Leallah’s long, sweeping stride carried her to victories in a Belmont Park allowance, Monmouth’s Colleen Stakes, the Arlington Lassie Stakes, and Jamaica’s Astoria Stakes. She concluded her 1956 season with a victory in Keeneland’s seven‑furlong Alcibiades and was voted the championship over a good group of fillies that included Romanita, Alanesian, and Lebkuchen. “She was developed by personable young MacKenzie Miller, who also produced Dr. Eslie Asbury’s Lebkuchen (1956 Selima Stakes winner) and clearly knows something of equine didactics,” recorded Charles Hatton in the American Racing Manual of 1957. New York was starting to take notice of the quiet Kentuckian.

At the same time, Mack Miller was taking notice of New York’s racing scene, and he liked what he saw. “One of the things I enjoyed about my first days in New York was walking through the paddock to saddle a horse. And there would be the Whitneys and Mrs. (Isabel Dodge) Sloane, the Wideners, James Cox Brady, Paul Mellon. One thing that impressed me most was that those wonderful people who had supported this game all of their lives and made it what it is today‑‑they would call you by name and speak to you. They would say: `How are you, Mack?’ or Joe, or whoever it was. Being a country boy, that was terribly impressive to me,” Miller said.

He said he spent those early New York years “trying to keep my mouth shut and my eyes and ears open. I thought it was the best way for a dumb guy like me to get along in life. I learned an awful lot from observation and association. I always enjoyed seeing good horse trainers perform, and I saw a lot of good horse trainers in New York.”

Miller also learned early to employ the best riding talent he could get his hands on‑‑jockeys like Eddie Arcaro (who rode Leallah in most of her races), Bill Hartack, and John Longden‑‑a practice he would follow years later with Jorge Velasquez, Patrick Day, and Jerry Bailey. “I thought Arcaro was as good as ever came down the road. But I don’t think that there’s a great deal of difference‑‑we had good riders then and we’ve got good riders now. I can’t see much difference‑‑there’s just more of them.” Miller said he always looked for riders with good hands, a fine sense of rhythm, and quick reflexes. For those riders whose work pleased him, he was steadfastly loyal and highly respectful of their abilities as horsemen.

The Aiken Training Center ©Joe Bailey

During 1960 and 1961, Miller followed the advice of two friends‑‑advice that would change his life forever. First, Jim Maloney touted him on Aiken as the ideal winter home for his stable. The following year, Miller tested the waters, splitting his stable between Aiken and Keeneland. “That was my last winter in Kentucky, because Aiken is the best place I know for a racehorse,” Miller said. “The water is good, and we have a distinct change in climate, which I think is very, very beneficial to racehorses. We have cold nights sometimes and some frost, and we have early springs. And we have a marvelous surface to train on. You put a marvelous foundation under your horses, and very few horses break down here.”

Early in the spring of 1961, fellow trainer and friend E. Barry Ryan decided to take a sabbatical in Europe and asked Miller to take over the training of three young horses he had just purchased for industrialist Charles Engelhard, whose racing success until then had been confined to England and South Africa. These three horses represented Engelhard’s first attempt to crack the American racing scene, and he traveled to Aiken to meet his potential new trainer and get Miller’s evaluation of the horses.

“One was a filly named Tan Jane, by Summer Tan‑‑his wife’s name was Jane. And I said: `Tan Jane is sort of a frantic filly, but she’s beautifully sound. It’s just a little early to predict what she’s going to do,’ because it was early in her two‑year‑old year. And there was Nassau Hall. He was from the first crop of Nashua‑‑he had an impediment in his rear end and he didn’t move too well. And I told him: `This colt needs to be castrated.’ And he said: `My God, you’re the damnedest man I ever saw. I don’t hardly know you, and you want to cut my horse!’ And I said: `I have to be honest. He’s not right behind, and I think gelding will help him.’

“And then he had a horse that I believe may have been by Blue Swords‑‑he had terrible ankles. And I said: `That horse you can give away, because he’s not gonna make it.’ And he said: `You’re the frankest man I’ve ever talked to.’ And I said: `I can’t be any other way, I’m sorry.’ ” Miller and Engelhard talked for about an hour, and, as the owner returned to his car, he told his new trainer: “Well, you can cut that horse if you think that’s best. I never interfere with my trainers.”

But Engelhard insisted that things be done right. Like the other barons of Thoroughbred racing, such as Greentree and Bwamazon, he wanted his own private stabling facility in Aiken. He purchased almost three acres of land adjacent to the training center for about $25,000 and hired a local contractor to do the job. Miller had the center built to his specifications. “This main barn is sort of a copy of Keeneland barns, where I cut my teeth,” Miller said. “It has 33 horse stalls, a little office, a little tack room, a little utility room. And on the other end we have a feed room.

The bunk house in Aiken ©Barry Bornstein

“And then when things were growing, Charlie said: `I think we’ll build another barn.’ I said: `I don’t think we ought to have any more horses, Charlie, this is big enough.’ He said no, that we’d build another barn. So I got rushed into building the nine‑stall barn, which gets sun all day from the east to the west. It’s a lovely little barn, the warmest barn we’ve got. Now we have 42 stalls and a bunk house, where my assistant has a little office.”

Throughout Engelhard’s time and later with Paul Mellon, Miller set strict standards of practice and conduct for his stable employees. He always was a stickler for details‑‑perhaps a holdover from his military days and a hallmark of all top trainers‑‑and he insisted on cleanliness and sobriety. In exchange, his employees were paid weekly, with fringe benefits far above the average. Miller hoped, as well, that he instilled in them a sense of pride and self‑discipline. “A racetrack is a very free place, people do as they damn well please. But I don’t have a lot of people come in and ask for jobs that are bad. People come who know what I am and what I stand for.”

Among those who passed through Mack Miller’s barn as a groom and foreman was Neil Howard, the trainer of 1990 Preakness Stakes (G1) winner Summer Squall. “He is a great joy to me,” Miller said. “He worked from daylight to dusk, always worked harder than any other person because he wanted to be a horse trainer. And I almost felt he was my son, he was so dedicated. And now he’s a very successful horse trainer, and that makes me happy.”

At Aiken each year, Miller would receive the horses after they had been broken to the saddle, and he would evaluate both their physical and mental attributes, trying to pick out the ones that came closest to his idea of perfection. “When I look at a horse, I look, first of all, at the shoulder, proper ankle, and to see that his feet are properly straight under him,” Miller said. “I like a horse that has sort of a short back, and I like a good, long neck, an attractive head with some width between the eyes, a generous eye, and maybe an ear that’s not too long. I like for them to track perfectly when they walk. And I think it would be nice if all horses could have, when they walk away from you, a little rhythm in their rear end, a little sway, perhaps. Sounds like the perfect horse. And you run across them once in a while.”

Early in his tenure with Engelhard, Miller developed a regimen for the young horses that, while allowing for each horse’s individual talents and needs, he would continue to use throughout his career. After the initial evaluation, he would bring them along slowly, provide a good foundation of physical fitness, start them a couple of times at two to get them used to the competition, and start racing them seriously at age three.

“Horses seek their own level with respect to class, dirt or grass, long or short,” Miller said. “They dictate to us what their potential is and what they can and cannot do. If we had our druthers, each two‑year‑old would start once. Regardless of whether they won or didn’t, you’d have an educated horse. If you start in January with a three‑year‑old maiden that’s never run, he’s the dumbest thing in the world. But if you can run them once, they’re sharp as three‑year‑olds, and they get to the races in about 100 days‑‑if you’re lucky and don’t have any pit stops.”

Miller pulled in for an inordinate number of pit stops during his first three years with Engelhard. Of the 40 horses in Miller’s public stable, 18 were owned by Engelhard’s Cragwood Stable, and not one of them was doing any good at all. Miller was frankly embarrassed, and he called Engelhard after the 1964 Saratoga season to suggest that perhaps the wealthy owner should find a new trainer.

“He said: `You get on a helicopter at Kennedy Airport and fly over to Newark and Sam, my chauffeur, will pick you up and we’ll have lunch together and talk.’ Well, I got to the airport in about ten minutes and Sam said: `Mr. Engelhard is not feeling too good, and instead of the office we’re going to Cragwood (Engelhard’s New Jersey estate) in Far Hills.’ We had a lovely lunch with him and his daughters, and then we went into the study and closed the door.

“He said: `Now, what’s your problem?’ And I said: `Well, I came here to get out of your hair. I think maybe you ought to try somebody else‑‑we’re not doing much good, and it’s a little embarrassing for you, I think.’ And one other thing I said: `As this thing has grown, I was in hopes maybe it would become a private job, because you’re obviously interested, and you want to keep growing.’

“And he said: `Is that your problem?’ And I said: `Yes, sir, that’s it.’ And he said: `Well, you notify all those other people that you’re going to work for me privately on January 1. I’ll send my accountant and my lawyer to Belmont, and you can talk with them. Name your salary, whatever you think it’s worth.’ ”

The contract lasted a year and contained a clause that, if Engelhard wanted to make a change, Miller would be compensated until he could reopen a public stable. That clause was never invoked. “For some reason, from that moment on, the horses started running,” Miller said. “And the contract was up the following year, and he told me: `There will be no more contracts. You’ll work for me as long as I live.’ I worked for him 11 years, until he died.”

During that time, Engelhard acquired more property in Aiken, across a narrow lane from the barns. The land, which had belonged to F. Ambrose Clark and then to John Hay “Jock” Whitney, included a steeplechase course on which Clark had schooled his jumpers. The Aiken Steeplechase Association now holds the first meet of the steeplechase season there each March, and Miller finds it very useful as a gallop for his turf horses before he ships to New York.

The Miller home in Aiken ©Barry Bornstein

On the adjacent 15 acres, Engelhard decided one day to build Mack and Martha a winter home. “He just said to me one day: `I think we’ll build you a house. I want to give you a budget of so much money.’ We had seen a house in Kentucky we liked, with a cathedral ceiling and lots of light. So we copied it in a smaller version. Jane (Engelhard) even sent us some furnishings.”

Charles Engelhard was a man of many contradictions. He had taken his family’s small precious‑metals business, Engelhard Industries, and had turned it into a huge corporation. In some ways, his tastes were opulent, even excessive. He maintained large estates in New Jersey and Florida, flew around the world in his private jet, and indulged himself with large glasses of heavily iced cola, consumed one after the other, which may have contributed to his obesity, his ill health, and his premature death at age 54.

At the same time, Engelhard was quiet and reflective, a man of simple tastes in some matters. Once, when Engelhard invited Miller to Cragwood for the night while the industrialist’s family was away, they ate TV dinners and talked until midnight. Often, Engelhard would visit the Millers in Aiken, and he would have a simple lunch or dinner and spend the night at a nearby club.

The Millers also have a home in Versailles‑‑a small white cottage across the street from where the trainer grew up‑‑and Engelhard visited them there on a miserable November afternoon when he had one horse running at Garden State Park and another at Churchill Downs. “It was 14 above zero, and we had a big roaring fire, and Martha had fixed us a beautiful lunch of soup and chicken sandwiches, which he loved. And he said: `We’re going to go somewhere to see one of these horses run. Where do you want to go?’ ”

After an hour, the two men were still sitting in front of the fire, deliberating between Louisville and Cherry Hill, New Jersey. “I said: `Charlie, we’ve got to get the hell out of here and get on that plane, wherever we’re going.’ He said: `I don’t think we’re going anywhere. I’m very comfortable here.’ ”

Finally, around 3 p.m., they got on the plane, flew to Newark, called Churchill Downs, and found that their horse had won the two‑year‑old stakes that day by a pole. The horse at Garden State finished second. And Engelhard’s only response was: “Well, I enjoyed my lunch and my stay. It was a happy day for me.”

The two men were to have many more happy days together over the next several years. Miller and Engelhard had their first champion when Assagai was named the champion grass horse of 1966, his three-year-old season. A $24,000 Saratoga yearling purchase in 1964, the dark colt by Warfare out of *Primary II, by Petition, did not perform even moderately well at first. “He couldn’t run a yard on the dirt. He won two dirt races, but everybody’s entitled to two, a maiden and a non‑winners of two,” Miller said.

Switched to the grass in the late spring of his three‑year‑old season, after he had won his two dirt races, Assagai underwent an amazing change. He literally found his stride on the grass. “It is his action,” Miller was quoted in the 1967 edition of the American Racing Manual. “They say action makes the racehorse, and his is ideally suited to the grass. I cannot narrow it down any further, but the change is dramatic for him going from the dirt to the grass.”

Assagai’s new‑found action carried him to consecutive victories in Monmouth’s Long Branch Stakes, Aqueduct’s Tidal Handicap, and Saratoga’s Bernard Baruch Handicap. After a second‑place finish to Ginger Fizz in the Kelly-Olympic Handicap at Atlantic City on September 3, Assagai went off as the 5‑to‑2 favorite two weeks later in Atlantic City’s United Nations Handicap. Under Larry Adams, Assagai rallied powerfully through the stretch and caught Ginger Fizz in the final strides to win by a head.

Adams was again the saddle when Cragwood’s colt won Aqueduct’s Man o’ War Stakes on October 22, when he wore down Buckland Farm’s Gallup Poll to win by three‑quarters of a length. In his next start, in Laurel Race Course’s Washington, D. C., International, Assagai finished third, 3 1/2 lengths behind the French invader Behistoun, but he was clearly the best of his division. He won eight races, including six of his eight starts on the grass, and earned $244,239.

In the American Racing Manual‘s reference to Engelhard, he was described as a little‑known newcomer, but Assagai’s success whetted his taste for becoming well‑known at the major yearling sales. He played no favorites‑‑Saratoga and Keeneland both benefitted from his spending. Engelhard bought only the best, most fashionable bloodlines and was especially fond of offspring by the stallions Native Dancer, Northern Dancer, *Ribot, and Hail to Reason.

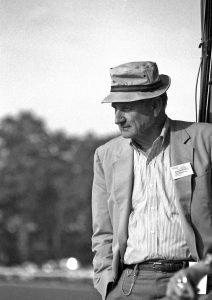

At Churchill Downs in 1993 ©Barbara Livingston

In 1966, Engelhard spent a world‑record $177,000 at Saratoga for a filly by Sailor out of Levee. She was named Many Happy Returns, but she produced few returns, winning only two of 24 starts and eventually becoming a broodmare of indifferent quality. In 1967, Engelhard was the top buyer at Keeneland, purchasing 10 horses for $622,000. This time, he fared better. One of his purchases was Mr. Leader, a hard‑knocking colt who went on to become a hard‑knocking stallion.

A $110,000 yearling purchase, the colt by Hail to Reason out of Jolie Deja, by *Djeddah, won the Jerome Handicap at three in 1969 and the Stars and Stripes, Tidal, and Oceanport Handicaps at four. Also in 1970, he finished a good third to Fort Marcy and Fiddle Isle in the United Nations. From 25 starts, Mr. Leader won ten races and earned $219,803.

Mr. Leader certainly was a nice horse, but Engelhard hit the jackpot in 1968 when he spent $84,000 for a big Northern Dancer colt out of Flaming Page, by Bull Page. Engelhard named him after Waslaw Nijinsky, the late Russian ballet star, and Nijinsky II certainly had all the grace and style of his namesake. Sent to the renowned Irish trainer Vincent O’Brien, Nijinsky II was undefeated in five starts as a two‑year‑old and was named champion in both England and Ireland. In 1970, Nijinsky II was Horse of the Year in England as well as the champion three‑year‑old in both England and Ireland.

He scored a convincing sweep of England’s Triple Crown‑‑the Epsom Derby, the Two Thousand Guineas, and the St. Leger Stakes‑‑to become the first horse since Bahran in 1935 to win the three races and the last one to do so. He also added the Irish Sweeps Derby and the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth II Stakes. “His biggest thrill was Nijinsky being champion,” Miller said. But the defeats that ended Nijinsky II’s career were bitter ones for Engelhard, who was in the final months of his life.

On October 4, Nijinsky finished second as the 2‑to‑5 favorite in the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, beaten narrowly by the 19‑to‑1 Sassafras (Fr) after a long drive through Longchamp Racecourse’s straight. Miller, who had attended the race, flew back with O’Brien and Engelhard on the owner’s private plane.

“He had been talking privately in the front of the plane to Vincent. I didn’t know what they were talking about,” Miller said. “We dropped Vincent off at Shannon (airport in Ireland), and he called me to the front. And he said: `Vincent wants to run this son of a gun two weeks from now in some big race in England. That’s against my better judgment‑‑I don’t think we should.’ And I said: `Why don’t you change your stance and ask him not to run? The Arc is the most killing race in the world.’ And he said: `Well, I never interfere with my trainers.'”

O’Brien ran Nijinsky II in the Champion Stakes, where he was defeated by long shot Lorenzaccio and soon was retired to stud after the only two losses of a tremendous career. Standing at Claiborne Farm, Nijinsky II also has had a tremendous career at stud and appeared certain to pass his sire, Northern Dancer, as the all‑time leading sire of stakes winners.

Engelhard never interfered with Miller, either, over decisions involving the training and placing of a horse. But he did sometimes insist that Miller take a horse that he did not really want. Such was the case with a rather pathetic‑looking specimen who arrived at Miller’s training center in Aiken in late 1968 after a lengthy boat ride from South Africa, where he had been a champion. His name was *Hawaii.

“A champion here and a champion there are two different things. This horse won’t do in America,” Miller had told Engelhard on the phone. His worst fears were confirmed when the horse came out of 60 days in quarantine. “He was the most emaciated horse. His feet hadn’t been trimmed, and he was a rack of bones,” Miller recalled. “He took it very hard, but we brought him here to Aiken and turned him out in a little paddock and let him play, and we got him cleaned out real good.”

The following spring, when the horse by Utrillo II out of Ethane, by Mehrali, was five, *Hawaii amazed Miller with his ability. “He had blossomed into a magnificent horse. He trained as good as any man’s horse on the dirt, but I ran him once on it, and he was beaten. I didn’t try it again‑‑he resented the sand. But he was the best‑striding horse I ever saw, covered a lot of ground and had a great disposition. He never got rattled.”

Miller had been told by *Hawaii’s South African trainer that the horse wanted short distances. Not so, Miller found out. In 1969, *Hawaii won six of his ten starts, progressing from 1 1/8 miles to 1 1/2 miles by the end of the season. He took the Stars and Stripes Handicap at Arlington Park, the Bernard Baruch at Saratoga, the United Nations and Sunrise Handicaps at Atlantic City, and the Man o’War Stakes at Belmont. Again, Miller lost the D. C. International at Laurel‑‑this time to an English‑owned horse, Karabas (Ire)‑‑with *Hawaii finishing second by 1 1/2 lengths. His total earnings were $279,280, and Cragwood Stable finished fourth in 1969 overall North American earnings with $827,305.

Miller trained other good horses for Cragwood through those years. Red Reality, a personal favorite of Miller’s, was a tough handicap horse, adept on the dirt as well as the grass. Miller and Engelhard made their only start in the Kentucky Derby in 1968 with stakes winner Jig Time, who finished sixth behind Dancer’s Image. Protanto won the 1971 Whitney Stakes at Saratoga; Rest Your Case won the Hopeful Stakes there the same year. Another impressive stakes winner was Tentam, who‑‑like *Hawaii‑‑Miller did not want in his barn.

“We had had a two‑year‑old called Raise Your Glass, by Raise a Native‑‑a nice medium‑sized horse who could run. I ran him in the Tremont Stakes at Aqueduct, and he dead‑heated with a horse called Tamtent that Angel Penna, my friend, trained,” Miller said. “And the following January, I went to the sale in Florida. And Charlie said: `There’s a full brother to Tamtent, and I want you to buy him.’ Well, I looked for him for three days, and I couldn’t find him. Nobody knew where he was stabled. And I finally located him at Horatio Luro’s barn at Hialeah.”

Miller found a horse so tiny that he looked like a weanling. He called Engelhard just before the sale started that evening and said: “That little fellow, you don’t want him. He’s perfectly clean, but he’s a midget.” Engelhard responded: “Well, you just do me the favor and buy him.” So Miller paid $48,000 at the 1971 Florida sale of two-year-olds and shipped the little fellow to Aiken.

Tentam started growing but never got over 15.2 hands or so. “But in the summertime, before Saratoga, this horse could beat anything, any horse I had. He was a dream. He bucked his shins, but he broke his maiden at two. And from three on, he was a corking little horse. He’d run on the grass, he’d run on the dirt, he’d run short, he’d run long.”

As a four‑year‑old in 1973, racing for Engelhard’s estate and later for Windfields Farm, Tentam zipped six furlongs in 1:09 2/5 over a sloppy Aqueduct track to beat Spanish Riddle in the Toboggan Handicap. He won the Metropolitan Handicap at a mile on the dirt, defeating Rokeby Stable’s Key to the Mint. He won the United Nations Handicap at 1 3/16 miles on the grass. And he and Red Reality each won a division of Saratoga’s Bernard Baruch at 1 1/8 miles on the turf.

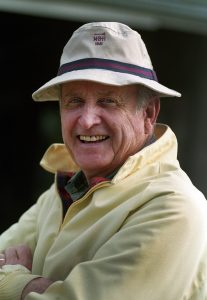

In 1995. ©Tod Marks

Perhaps his most valiant race was in the Man o’ War, where he went down to defeat to Secretariat‑‑but not without a fight. “He was the cutest thing that God ever created and the most tenacious horse you’d ever seen,” Miller said. “He tried Secretariat in the Man o’ War two distinct times, once at the half‑mile pole and again at the three‑sixteenths pole. He tried like hell. He was beaten five lengths, but he was second. He wanted to be a racehorse, and that’s what he was. We sold him for $2.2‑million to Eddie Taylor for stud, after Charlie died.”

Charles Engelhard died on March 2, 1971, but not before making one more score at the yearling sales. At the 1970 Keeneland summer sale, he picked up another son of Hail to Reason‑‑as Mr. Leader had been‑‑out of the stellar mare Cosmah, from a female line that had produced Northern Dancer. (Natalma, Northern Dancer’s dam, was a half‑sister to Cosmah.) The price was $100,000, and thanks in large part to Engelhard’s open checkbook throughout the 1960s, that was no longer an astronomical price to pay for a horse.

The colt was named Halo, although he certainly never wore one. While his owner would not live to see him race, Halo would add a fascinating postscript to the Engelhard saga. “When he was four, I guess, David McCall, the racing manager, said he was going to sell that horse to Irving Allen in England. He was going to get $600,000 for him, I believe, for stud. And I said: `Well, David, this is not the proper time to do this. It’s summertime, and he’s not going to be bred until next year.’ He said: `Well, I’m going to sell him.’ And I said: `Well, that’s your privilege. But you must declare that he is a cribber. Cribbing is not good, not accepted over there.’ ”

Lexington horseman Tom Gentry, acting on behalf of the buyer, consummated the deal while Miller was at Saratoga. He would run the colt one final time, at Belmont Park, before the horse was to be shipped out, and the buyer’s representative flew to New York to watch his race.

“He got beat‑‑he was second. And we were walking back to the barn, he and I, to see this horse cool out. And I said: `This is a bloody nice horse, but he’s a cribber, which you know.’ And he said: `What?!’ And I said: `Well, it was declared by me to Mr. Gentry and to David McCall.’ ”

Litigation ensued‑‑each side suing the other‑‑and Halo was turned out for several months at Tom Gentry’s farm while the issues were sorted out. While there in the winter of 1973‑74, he underwent a personality change that Miller has never been able to understand fully. When Halo had first gone into training at Aiken, Miller had had a devil of a time with the young horse. Halo had a mind of his own and, like a young puppy, often ran away from home. “He used to dump a rider occasionally and run across the road into John Gaver’s (Greentree Stable) yard, and John would call and say: `Get that black son of a bitch out of here‑‑if you don’t, I’m going to shoot him!’ I never considered him mean, but he was cantankerous,” Miller said.

Early in 1974, Miller asked the executor of Engelhard’s estate to clear up the mess surrounding the horse. Because he could not be bred, it only made sense to get the horse off Gentry’s farm and put him back in training. The deposit was refunded, and Halo returned to Miller’s barn. But the trainer was shocked by the change in his disposition. “He had gotten ornery as the dickens in that five months or so,” Miller said. “He literally hurt people. They had to leave a muzzle on him‑‑he would just pick people up and throw them.”

But Halo trained well, and ran well. After two defeats at five, he won a turf allowance and then took the Tidal Handicap (G2) on Aqueduct’s turf course. “Before the United Nations Handicap, I called Mr. Taylor in Canada and said: `I’ve got a horse called Halo that’s got a hell of a pedigree. He’s a stakes winner, and I think you ought to buy him. He’s going to run in the United Nations.’ ” Miller appraised the horse at $1‑million, and Taylor purchased him. He won the United Nations in Windfields’s colors on August 30, 1974, but bowed a tendon on Atlantic City’s soft turf and was retired to Windfields’s Maryland farm.

“They gave me a breeding right‑‑that was incorporated into the deal. And you know what? You can’t sell the darn things. It’s funny; he’s a marvelous sire,” Miller said. Indeed, though underrated throughout his career, Halo is a two‑time leading North American stallion (1983 and 1989). He has sired Sunday Silence, the ’89 Horse of the Year after his victories in the Derby, Preakness, and Breeders’ Cup Classic (G1); Glorious Song, a Canadian Horse of the Year; ’83 juvenile champion Devil’s Bag (a full brother to Glorious Song); and ’83 Derby winner Sunny’s Halo.

Miller also picked up a new owner in the deal. Taylor had purchased both Halo and Tentam from Engelhard’s estate and left them with Miller. He later asked the trainer to take over *Snow Knight, the 50‑to‑1 winner of the 1974 Epsom Derby (Eng‑G1), in whom he had purchased a half‑interest. “He’d sent him over to his racing stable in Canada, and he was a rogue at the starting gate,” Miller said. “He wanted me to take him and see if I could rebuild his confidence and run him the following year. He came in November, and he was sort of a sad-looking, sick horse. He had run down on his hind heels and had some infection in them. He didn’t look good. An I immediately called the farm and said: `I think this horse ought to go to stud‑‑I don’t think he’s going to make you a racehorse.’ And they said: `Well, you’re going to have to keep him.’ ”

Taylor wanted to get back some of the million dollars he had invested in *Snow Knight‑‑and so he did. Aiken’s mild winter weather proved to be a tonic for the horse, who by springtime looked like a pretty nice chestnut racehorse. Then, Miller had to figure out some way to change *Snow Knight’s bad gate manners. “Every day‑‑every day!‑‑we went to the gate and stood and looked and walked around the damn thing. He finally overcame this enormous fear of the gate. We heard that he had been tied to the gate in England and made to stand there, and he hated it. But I had a good rider, Jill Gordon, and I had a marvelous assistant trainer in those days, and finally we got him schooled for New York before we left here. You had to load him, but he would tolerate it.”

Miller decided that *Snow Knight would make his 1975 debut in a race at the end of the Aqueduct spring season so that he would be ready for Belmont. *Snow Knight made several schooling trips to the paddock and never turned a hair. Miller called Taylor at his home in the Bahamas and suggested that he travel to New York to watch his horse run; Taylor agreed. “And we saddled him, and he walked on the track‑‑and threw the rider higher than John Glenn. He ran off, and we had to scratch him. And I said: `Mr. Taylor, I’m a man of my word, and I swear this horse has been perfect. I apologize. There will be another race in two weeks at Belmont, and on his home ground, I think he’ll run better.’ ”

*Snow Knight indeed ran better. The four‑year‑old by Firestreak out of Snow Blossom, by Flush Royal, won an allowance at Belmont on June 18. After finishing second in another allowance, *Snow Knight acted up around the gate for the U. N. Handicap and never got into the race, finishing last of nine. The colt then went on a rip, winning the Seneca Handicap (G3), the Brighton Beach Handicap, and a division of the Manhattan Handicap.

Now a seasoned competitor, *Snow Knight went up against top‑level competition in Belmont’s Man o’ War Stakes (G1) on October 11. Under Jorge Velasquez, *Snow Knight was rallying in the stretch when One On The Aisle came out twice and bumped him. One On The Aisle won by 1 3/4 lengths over *Snow Knight, but the Rokeby gelding’s number came down when the stewards upheld Velasquez’s foul claim. In his next start, *Snow Knight won Woodbine Race Course’s Canadian International Championship Stakes (G1), finishing more than two lengths ahead of Dahlia, who was fourth and clearly past her best efforts that year. In his final 1975 start, *Snow Knight finished sixth in the D. C. International after bobbling on Laurel’s backstretch, but his six victories from nine starts won him the year’s grass championship.

In taking on E. P. Taylor as a client, Miller had once again opened a public stable. Jane Engelhard was cutting back her operation to just a few mares and a few horses in training. She and Miller worked out an arrangement under which he would remain on her payroll at full salary, but she would receive all of the per‑diem payments he billed to his other clients. The arrangement continued for two years after Engelhard’s death.

At the same time, Jane Engelhard was determined to follow through with her husband’s wishes that Mack and Martha receive the house and the surrounding 15 acres of land in Aiken. The property was appraised, and a deal was worked out for the acquisition. A couple of years later, Miller purchased the remaining 55 acres and the two stables.

In 1976, when trainer Elliott Burch suffered a self‑described nervous breakdown and Virginia breeder and philanthropist Paul Mellon needed a new trainer, Jane Engelhard suggested Miller. She wanted to get out of the horse business completely, and Miller encouraged Mellon to buy a package of the ten horses she still had left. One was Upper Nile, who would win the 1978 Suburban Handicap in Mellon’s colors. Another was the broodmare Javamine, dam of Java Gold.

“I knew Paul Mellon long before I knew Jane, just to speak to, when his trainer was a fellow named Jack Skinner, who trained the jumpers and the flat horses,” Miller said. “Jack and I were pretty good friends. I used to go up and spend the night at Middleburg (Virginia) and see the horses, and I would speak to Mr. Mellon. Mr. Mellon was such a wonderful sportsman–so devoted to horses. I admired him from the start. I went to see the Arc (which Mellon’s Mill Reef won in 1971). Elliott was his American trainer, and Elliott took me as his guest on Paul’s plane. That was a great treat.”

Mellon and Miller at Saratoga in 1993. ©Barbara Livingston

When Mellon apparently concluded that Burch would be unable to return to his post, Rokeby’s owner asked Miller to assume the post. This private training job would be different from the previous one. Most significantly, Paul Mellon bred most of his horses, while Engelhard had purchased his runners, principally at yearling sales. That could have been a burden if the owner had very set ideas about breeding patterns and crosses. Instead, Mellon was receptive to Miller’s recommendations about injecting fresh blood, starting with the broodmares he acquired from Engelhard’s estate.

As had been Mellon’s practice with Burch, Miller was given a great deal of authority over how the young horses were raised and broken on Mellon’s farm before they were shipped to Aiken. “We started, for one thing, producing our horses in sheds. When they were weaned in the fall, of course, the colts and fillies were separated to different parts of the farm. And I said to Mr. Mellon: `I’d like to build some run‑in sheds where these horses can stay out all the time except when they’re ill.’ ” Within two months, the paddocks had their run‑in sheds, which are still used today.

Miller also employed an old trick he had learned in his first days at Calumet Farm‑‑acquired from no less of a source than Ben Jones‑‑on how to get the young horses ready for rigorous training at the track. “At Calumet, they would run the colts together till they went to Florida, almost, and they would come in with the worst scars and cuts. And I asked Mr. Jones when I was there: `How can you turn these beautiful horses out to fight like that?’ And he said: `That’s what they need to be competitive.’

“They are tended to every day. They have their feet picked, and they are checked for a fever‑‑any sickness, they go right into a barn, and when they’re well they come out again. These colts get to be pretty strong and big, and they fight like hell. But I think it makes better racehorses. I’m so happy that Mr. Mellon allowed me to do it.”

Although into the 1990s they had never campaigned a champion together, Mellon and Miller sent out many major stakes winners‑‑horses who have run on the dirt or on the grass; tough handicap horses and precocious two‑year‑olds; and several fine fillies that have added new depth and strength to Rokeby’s select broodmare band.

One of the best was Winter’s Tale, who came to Miller as a two‑year‑old in 1978 but had enough nagging little problems that he did not get to the races until the following year. By Mellon’s Belmont Stakes (G1) winner Arts and Letters out of Christmas Wind, by Nearctic, Winter’s Tale was gelded. Neither Mellon nor Miller had any qualms about cutting a horse if they believed the result would be a better racehorse. If he did not perform on the track, they reasoned, the horse would not make much of a stallion prospect, anyway.

Though Winter’s Tale was just an “average‑looking horse,” Miller discovered the gelding had some real ability when he began training him at three. “He was not a fluke‑‑he could run. He also had a better temperament than most Arts and Letters. But he developed a sinus condition, which is hard to treat because there’s no circulation up there. We did an operation on him that’s 100% effective, in which they drill little holes in the upper sinus cavity, insert a plastic tube, and treat it with antibiotics right into the little holes. And I want to tell you, he got over it.”

The horse recovered quickly enough to race several times in the fall of 1979 as Miller sent him “up the ladder”‑‑through his allowance conditions, as the trainer tried to do with all of his horses before sending them into stakes races. By the time Winter’s Tale was four, he was ready for bear. Miller entered him in a race at Belmont as part of an entry with a nice stakes horse called Music of Time, “and Winter’s Tale galloped‑‑he beat the hell out of Music of Time. And that confirmed my thought that he might have a future.”

The remainder of 1980 included wins in New York’s three richest handicap races: The Marlboro Cup, the Suburban, and the Brooklyn‑‑the only horse to win all three in the same year. He won the Nassau County Handicap as well and earned $462,800 for the year, nearly half of Rokeby’s total earnings of $1.06‑million. In some years, that gaudy record would have been sufficient to win an Eclipse Award, but Winter’s Tale had the bad luck to come along in the same year as Spectacular Bid, who was perfect in nine 1980 races and was voted champion older male and Horse of the Year.

Winter’s Tale also had some bad luck with an assortment of odd ailments. In addition to the sinus problem, he severely injured his back and had to be turned out for about six months at one stretch; through much of 1982, he simply could not be trained. But he returned in 1983 to win both the Suburban and Nassau County handicaps for a second time before being retired.

Miller was about to enter the most successful and profitable period of his association with Mellon, a period that began with the double‑barreled threat of Fit to Fight and Hero’s Honor. By Northern Dancer and out of the Graustark mare Glowing Tribute, Hero’s Honor fit the Rokeby mold: Bred in Virginia by Mellon, he excelled on the grass. But Fit to Fight did not fit the pattern. Bred by Miller’s friends Robert B. Congleton and Robert E. Courtney, the colt by Chieftain out of Hasty Queen II, by One Count, was purchased by Mellon for $175,000 at the 1980 Saratoga yearling sale.

Fit to Fight was brilliantly fast, but he also was slow to mature. Although he won the Jerome Handicap (G2) as a three‑year‑old in 1982 and the Stuyvesant Handicap (G2) a year later, he ran the best races of his career at five. “Maybe he had some problem that none of us knew about, but he was never very strong at two. He was always a year behind‑‑that’s why I ran him as a five‑year‑old. And that’s when he did all the damage,” Miller said.

He indeed did his share of damage in 1984. He swept the New York handicap triple‑‑the Met at a mile, the Suburban at 1 1/4 miles, and the Brooklyn at 1 1/2 miles. Despite the Bold Ruler blood coursing through him, he won by increasingly larger margins as the races grew longer. He prevailed by a head over the swift A Phenomenon after a long drive in the Met; he won by 3 3/4 lengths in hand under Jerry Bailey in the Suburban; and trounced his opponents by 12 1/2 lengths over a sloppy track in the Brooklyn. With dominating performances, he became only the fourth horse to sweep the series, joining Whisk Broom II (1913), Tom Fool (1953), and Kelso (1961). One of Fit to Fight’s victims in the Suburban was Wild Again, who would win the first Breeders’ Cup Classic that fall. “I think he was more comfortable going 1 1/8 miles, but he won the Brooklyn and the Suburban,” Miller said of Fit to Fight. “And he was absolutely bone‑sound. He was as sound a race horse as ever walked.”

His stable‑mate, Hero’s Honor, was no threat to him on the main track. The Northern Dancer colt cared only for the grass. In addition, as a kindergarten teacher might note, he had an attitude problem and had difficulty working with others. “He used to dump a rider every day,” Miller said. “He would gallop and prop and wheel and unload. And if it were into the inner rail or the outer rail, he didn’t give a damn. But he had an awful lot of talent.”

How to harness that talent and energy was a puzzlement to Miller, but his good friend, Jim Maloney, came up with a simple solution. “He said: `I want to give you some advice with that bum. Instead of letting him hurt himself, go out and buy an old gelding of some kind and let him be a companion.’ I didn’t have to buy one, I had one‑‑a Secretariat horse that Mr. Mellon had, named James Boswell. Beautiful horse but couldn’t run too fast.” James Boswell became a constant companion to Hero’s Honor, just as Boswell the 18th century biographer, had been practically a shadow to Dr. Samuel Johnson. “They walked together, galloped together, worked together‑‑they were inseparable. James Boswell turned this Hero’s Honor into a first‑class racehorse. First class, he was. His disposition, I don’t guess it ever mellowed. I think he never enjoyed being alone, and James Boswell was literally a security blanket for him,” Miller said.

Hero’s Honor was secure enough to rip through the Fort Marcy (G3), the Red Smith (G2), the Bowling Green (G1) Handicaps in New York as well as the United Nations Handicap at Atlantic City. Two weeks after the U. N., Hero’s Honor raced in the Sword Dancer Handicap (G1) over a soft Belmont turf course, led to the top of the stretch, but then folded, finishing last of 11. Still, Hero’s Honor won $424,050 for the year, and with Fit to Fight accounted for more than half the $1.8‑million that Rokeby Stable earned in 1984.

“And then we sold them to Will Farish (owner of Lane’s End Farm near Versailles, Kentucky) for quite a lot of money for stud. The horse business was very good at the time, horses were very expensive, so we got a very, very good price for them. I think we kept four shares in one and six in the other, so we’d have something to breed to,” Miller said. Neither horse was particularly successful at stud, and Hero’s Honor subsequently was exported to France.

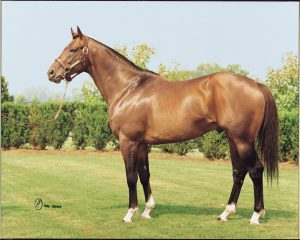

In 1986, Mellon sent Miller a two‑year‑old by Rokeby’s 1972 three‑year‑old champion, Key to the Mint, and out of Javamine, the mare that the trainer had urged his new owner to buy from Jane Engelhard in 1976. This one would be special; in Mack Miller’s estimation, the best he ever trained. The colt’s name was Java Gold.

Normally, Miller did not race his two‑year‑olds much and, if he had his preference, would start them only once at two, and then only to give them some racing savvy for when they began their three‑year‑old campaigns. Java Gold was by no means precocious, but his talent was obvious, and Miller nurtured it slowly through his two‑year‑old campaign, in which he won three of seven starts and $287,532.

“Java Gold was not a very big horse. He was a little narrow across his quarters, but confirmation‑wise, he was fine. He had a good shoulder, which is so important to a racehorse. He had a pleasant outlook. And, believe it or not, he was a very fast horse,” Miller said. The colt was fast enough to compete in Saratoga’s juvenile races, finishing third in the Saratoga Special Stakes (G2) and fourth in the Sanford Stakes (G2). He finished a promising second in Belmont’s Cowdin Stakes (G1), a length behind Polish Navy, but then ran evenly to finish fourth in the Champagne Stakes (G1), which Polish Navy won by a nose over Demon’s Begone.

Miller passed up the Breeders’ Cup races at Santa Anita Park that fall and put Java Gold on target for Aqueduct’s Remsen Stakes (G1) at 1 1/8 miles on November 22. Java Gold ran a thoroughly professional race as he stalked pacesetter Drachma into the final turn, shook off a determined challenge by Talinum after taking the lead, and drew clear in the final sixteenth of a mile to win by 2 3/4 lengths. His time under Pat Day was a very respectable 1:49 3/5 over a fast track. “Mr. Mellon was there and I said in a very subtle way: `I think this horse has a future around two turns.’ That was the key to him,” Miller said.

The victory was sufficiently impressive that the New York media‑‑who generally have always liked and respected Miller‑‑began talking about Java Gold for the 1987 Triple Crown. But that put Miller and Mellon in something of a quandary, because they did not want to be pressured into running in the Derby or any of the other Triple Crown races. Mellon had won an American classic, the 1969 Belmont Stakes with Arts and Letters, and Miller had started a horse in each of the classics‑‑Cragwood’s Jig Time ran sixth in both the 1968 Derby and Preakness, and Engelhard’s Zulu Tom finished ninth in the ’72 Belmont.

Mellon and Miller won the Kentucky Derby in 1993 with Sea Hero – Jerry Bailey, up. ©Barbara Livingston

Although the Kentucky‑born trainer always wanted to win a Derby, he nonetheless believed that the race demanded too much too early in a horse’s career. Fortunately, his owner shared his view, and he and Mellon decided over the winter that they would not go to Churchill Downs for the 113th Kentucky Derby. The racing media disapproved loudly, to put it mildly, but circumstances would have kept Java Gold away from the ’87 classics no matter how Mellon and Miller had decided.

“He wintered in Aiken, and he looked so good and trained well,” Miller said. “And I said: `I’m going to ship him up and run him in early April and try to do the Preakness with him, because I think two turns is really going to be his cup of tea. And his first two races were sprint races, which he won quite convincingly, and I was tickled to death.” In one, Aqueduct’s Best Turn Stakes at six furlongs on April 18, he defeated good sprinters in 1:09 2/5.

But New York had horrendous spring weather, and the conditions exacted a toll on Java Gold, who developed a fever and a cough. Miller was greatly disappointed initially that Java Gold would not have a shot at the Preakness and perhaps the Belmont, but he soon got over it. “It was the greatest thing that ever happened‑‑the greatest. Because I had to stop and that was a godsend,” Miller said. “He was going to end up, if I continued, being very light. But when I gave him the second training, after he’d gotten over the sickness, he was a different animal altogether. He had spread out, he had put on flesh, and he was a corking‑looking racehorse. So the good Lord had intervened and allowed me to have this really top‑class three‑year‑old.”

Because Java Gold had lost so much time and because he appeared to prefer longer distances, Miller brought him back that summer in a 1 1/16‑mile allowance race. The trainer instructed Day, who had flown in from Chicago to ride, to give Java Gold a good race but not to get into him too much with the whip; bigger and better races lay ahead for them, and this allowance race was only a warm‑up. Java Gold finished second, and Day reported that, if he had hit the colt just once, he would have won by five lengths. In his next start, at Belmont on July 10, Java Gold indeed won by daylight. “And from then on, it was cake and gravy‑‑it was wonderful,” Miller said. “What a joy to have.”

Java Gold was shipped to Saratoga, where he met a very tough and well‑balanced field in the Whitney Handicap (G1) at 1 1/8 miles on August 8. The narrow favorite at 2‑to‑1 was Robert Meyerhoff’s talented but quirky Broad Brush, who most recently had won the Suburban. Java Gold, his reputation barely tarnished by his absence from stakes competition, was 5‑to‑2, and also in the field was fellow three‑year‑old Gulch, who was making his first start after winning the Met Mile and finishing third in the Belmont.

Java Gold steadily advanced down the backstretch, and Day asked him to run leaving the final turn. Gulch took the lead in the stretch, but Java Gold wore him down and won by three‑quarters of length. Broad Brush was third, another 2 1/4 lengths behind Gulch. It was a fine race but only a prelude to what was to come two weeks later.

Mack Miller and Jerry Bailey, Travers Stakes, Saratoga, Racecourse, 1993. ©Skip Dickstein

The 1987 Travers Stakes became what MacKenzie Miller described as the most satisfying race of his training career. For years, he had been coming to Saratoga, saddling horse after horse under those stately elms, but he had never managed to win the race commonly known in New York as the “Midsummer Derby.” This year would be different, though it would not be easy. The Travers, after some spotty years in the 1980s, attracted a stellar contingent on August 22 to run 1 1/4 miles for the winner’s share of the $1,123,000 total purse.

Bet Twice, the Belmont winner, and Derby victor Alysheba had shipped in after their titanic struggle in Monmouth’s Haskell Invitational Handicap (G1), which Bet Twice had won by a neck. Joining the field of nine were Polish Navy and Cryptoclearance, the respective first and third finishers in Saratoga’s Jim Dandy Stakes (G2), and Gulch. Alysheba went off as the 5‑to‑2 favorite, with Java Gold at 7‑to‑2. The race was further complicated by rains that turned the track sloppy and an anonymous phone tip that Alysheba would be given some illegal medication, although it was not clear whether the drug was intended to stop him or help him. As a result, guards were posted outside his stall all day.

Java Gold broke well from the third post position, but the speed quickly ran past him, and he was soon at the back of the field with Cryptoclearance while Polish Navy and then Temperate Sil set a strong pace, completing six furlongs in 1:10. “He was so far out of it down the backside, I nudged my boss and said: `My God, it’s too bad he’s going to get clobbered today.’ But he made this gigantic move, and my heart went in my mouth. And at the quarter pole, I knew he was going to win.”

Soon after entering the final turn, Java Gold unleashed a powerful piece of acceleration and flew toward the leaders. Day angled him out as they entered the stretch to keep up his momentum, collared Cryptoclearance to grab the lead at the sixteenth pole, and drew off to win by two lengths. Polish Navy, who had held the lead at the top of the stretch, held on for third, 6 3/4 lengths behind Cryptoclearance, and Gulch finished fourth. Bet Twice and Alysheba, apparently paying the price for their epochal battle three weeks earlier in the Haskell, finished fifth and sixth, respectively.

“Pat Day’s ride was scary, it was so good,” Miller said of the ride by Java Gold’s jockey, who never has been a favorite of the New York racing press. “I can’t imagine any other rider persevering that long, and I think he knew in the back of his mind that once he started to run on the turn, he had a shot. I felt other riders might have said: `Oh, to hell with this. It’s a muddy, wet day; it’s only a million dollars, what the hell.’ ”

Miller believed deeply that he had the best three‑year‑old in the country that fall, and he was pressured in print to prove it by shipping to Louisiana Downs for the Super Derby Stakes (G1) and again meet Alysheba‑‑this time outside of New York, where Java Gold had run all of his races. Miller declined to ship to Louisiana and was again subjected to media criticism. Perhaps the most vitriolic attack was launched by Andrew Beyer of the Washington Post, who accused Mellon of unsportsmanlike conduct for keeping his horse at home.

“To say that Paul Mellon is a bad sport, with his enormous contributions to racing and enormous contribution to American society with his art and his museum‑‑that hurt me deeply,” Miller said. “In Java Gold’s particular case, we didn’t try to dodge anybody. But New York is our base. They give us stalls, and we’re obligated to do as much as we can to fulfill our obligation to them. I don’t think that I have to take a horse of that quality and go into Louisiana or somewhere else and perform. This program we had, I thought, was satisfactory.”

Java Gold proceeded to dismantle a field of four opponents in the Marlboro Cup on September 20, rolling by Polish Navy in the final furlong and winning by 2 1/4 lengths over Nostalgia’s Star. Miller felt confident as he entered the colt in a comparable field for the $1‑million Jockey Club Gold Cup Stakes (G1) on October 10. “I thought it was going to be easy,” Miller recalled. It turned into a disaster. Not only did Java Gold not win the race as the 3‑to‑10 favorite, he never came close to the venerable gelding Creme Fraiche, who crossed the finish line nearly five lengths ahead of the Rokeby colt. Pat Day had taken a strong hold of Java Gold early but, unlike the Travers, he took him wide around the first turn and kept him in the middle of the track. Java Gold passed tired horses in the stretch but‑‑as the Daily Racing Form chart footnote commented‑‑”without menacing the winner.”

“The first thing that entered my mind was that if Pat Day had not taken hold of him leaving there‑‑if he had let him run and gone to the lead‑‑he would have galloped. And Pat, after the race, said precisely that‑‑that if he had let him run, he would have won. He was choking him to death.” Poor tactics may have contributed to the loss, but they may not have caused it. When Miller returned to the barn, the horse was lame. X‑rays showed he had broken a bone on the outside wing of the right foot, and Miller never figured out just when or how it happened.

Although Java Gold had accomplished enough to win a championship in other years, the 1987 three‑year‑old title would go to Alysheba. The Derby and Preakness victor won the Super Derby and came within a nose of defeating the four-year-old Ferdinand in the Breeders’ Cup Classic at Hollywood Park. Given stall rest while the injury healed, Java Gold returned to training at Aiken in early 1988 and appeared to be progressing well. But, in his final workout before his scheduled four‑year‑old debut, he again came back lame and had to be retired. It was a sad ending for an outstanding racehorse, one of Miller’s favorites.

“But he was a fine horse. And I think winning the Travers was as exciting as anything I’ve ever done. I thought the Triple (Handicap Triple with Fit to Fight) was great, but the Travers is a thing that you dream of like the Kentucky Derby. I’ve watched it all my life, from Day One, with great enthusiasm, hoping that one day I could win the Travers. And I did,” Miller said. Java Gold, like Fit to Fight and Hero’s Honor before him, was retired to Will Farish’s Lane’s End Farm, and his first crop of two‑year‑olds went to the races in 1992.

In 1990, Mack Miller was again tempted to at least think about the Triple Crown, after his promising two‑year‑old Red Ransom had gone two‑for‑two the year before. He even shipped the colt by Roberto out of Arabia, by Damascus, to Gulfstream Park in Florida, to prepare him for what would have been, on Miller’s calendar, an unusually early three‑year‑old campaign. Red Ransom sustained an injury on the track, however, and never made the classics.

Eastern Echo ©Tony Leonard

That fall, Miller won Belmont’s Futurity Stakes (G1) with Eastern Echo, a colt he described as “a lovely, strong, fine racehorse. He was so sound. And I thought he was absolutely legitimate because he had a pedigree ten miles long and a great ability to run.” But the Damascus colt out of Wild Applause, by Northern Dancer, also sustained an injury and was forced into an early retirement.

The career‑ending injuries to two such fine colts led Miller to wonder again whether the fierce competition so early in a horse’s racing career are necessarily the best course. He laughed when he suggested moving the Triple Crown to the fall, but he was dead serious about not attempting it with anything but a sound, strong, legitimate contender. “I think when you consider that you are fooling with horses that, in most instances, are not even three‑year‑olds, you’re asking a hell of a lot of them.

“I want to have the proper horse who I think is good and sound and has a chance of standing the gaff‑‑that’s the main thing‑‑being able to take the grueling routine of starting in January and going to May. We have seen in our lifetime, as we all know, that some of them get there and then you don’t hear from them for a while. And I have a funny thing about that, wanting to take a horse and putting him through that, and then not having him for months or maybe the next year. But I want to reiterate that I would like to run in it with a legitimate horse that I think is capable of standing the preparation for it. Some things weren’t meant to be, maybe.”

Mack Miller is an anomaly in the racing business of the latter half of the 20th century because he spent most of his career as a private trainer. Other than Mellon and the Phippses, there are few families left who keep a trainer on the payroll. “It’s been unusual. I haven’t had any restraints put on me about how I run things. I make the decisions,” Miller said. “And I don’t think in those 28 years of private employment that I’ve ever had a cross word. You express yourself freely, and 99% of the time it’s accepted as the proper thing to do. It’s sort of comparable to the way trainers operate in England and Ireland and France, that you are held responsible for running this thing as best you can.

“I guess I have made some errors in judgment, sure. But I think it’s fair to say that when you work for these people, you do a lot of thinking privately before you do things‑‑you’re constantly planning ahead. The saddest thing in this business is that you have these accidents that horses have. It’s very difficult to call a fellow at 9 in the morning and say: `Your horse broke down.’ But fortunately, the two men that I worked for through these long years always accepted it better than anybody else I’d ever heard of. They’re genuine sports people. They understand that we’re going to have some bad things happen. But I think when you have a good thing happen and develop a good horse, that sort of pays for the grief you’ve had.”

The private training positions have certainly shaped his thinking on several matters. He despised year‑round racing, for instance, but he did not worry about it because his owners preferred to freshen the horses over the winter and could afford to do so. Winter racing in the Northeast, Miller said, is unnatural. “I don’t think the Good Lord intended for that to happen. I’ve never thought that racing in the wintertime in New York, Maryland, is healthy for horses, and I think it’s very difficult on the personnel who have to take care of them. But again, it’s economics. The state wants its money, and they dictate the policies‑‑certainly in New York. So we have to live with it.”

Despite some abortive efforts toward uniformity, the wide variety of medications rules was something else that racing has had to live with. “The drug thing is a big problem to me, maybe as big as we have, that we can’t be uniform. And I do think that we’re over‑raced. I do think so.” Miller is also dismayed at the changes in the great races that his horses have won in the past‑‑changes such as shortening the distance of events such as the Jockey Club Gold Cup from 1 1/2 miles to 1 1/4. “I never thought they would do that. I really never thought I would see it change in my lifetime. But it has. So maybe we’ll get Bute and Lasix and all that stuff. It’s not written in stone that we can’t have it. I don’t know what’s going to bring about the change in the medication rules in New York, but eventually I guess it will come. There’s so much pressure.”

Many of racing’s current economic problems, Miller believes, stem partly from the type of people coming into racing. “We have people in the business now who really don’t understand horses. Sometimes I think they got into it for the social aspect of it and of course the money, and not because they have a genuine love for a racehorse. We used to go and have lunch at the track whether we ran a horse or not. But now you go there, and there’s nobody in the box section. It’s a sad thing to me. I don’t know how they can re‑kindle the interest among the people.”

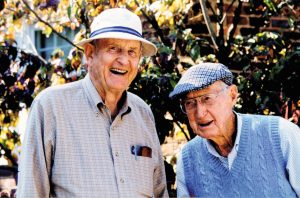

Mack Miller, left, and Dr. Smiser West at Waterford Farm in October, 2001. ©Anne M. Eberhardt

As the 1990s began, Miller’s years of experimentation in Thoroughbred breeding finally paid off, and he had Paul Mellon to thank for that, too. Miller and R. Smiser West have had a small commercial breeding operation for many years, and in 1991 they had about 20 mares whose offspring are bred for the Saratoga and Keeneland yearling markets. Every year, Rokeby Stable culls horses in training to make room for the yearlings, and one of those to be sold at the Belmont Park paddock sale in November, 1984 was Printing Press, by In Reality, who had a constriction in her throat and never raced.

Miller and West purchased Printing Press for $90,000, and her first two foals did not do too much. “And then we bred her to Majestic Light, and we got this little tiny filly, back on her knees‑‑she brought $35,000 at the Keeneland fall yearling sale.” The filly was Lite Light, winner of the 1991 Kentucky Oaks (G1), Santa Anita Oaks (G1), and Coaching Club American Oaks (G1). “You wouldn’t have given her stall space,” Miller said of the tough little filly, and shook his head in amazement. “That’s what I’m telling you about this damn breeding business. You cannot tell what’s going to happen.”

The same is true of training, of course. You don’t know what’s going to happen when the next group of two‑year‑olds shows up in the barn. Some are a pleasant surprise; some not. “I think sometimes the ones that have disappointed are the ones that had ability but no guts,” Miller said. “Train like Man o’War and come into the paddock and get washy and wet, and run their race before they get to the post.

“That’s just the nature of the game. Absolutely the way it was meant to be. We try to match the mares (to stallions) in some sort of logical fashion, but I have to tell you from experience: You never know what they’re going to look like when they come out. The Lord intervenes or luck intervenes and says, it’s not quite as good as you wanted, but there it is. If all of them could run, it would be no fun. You have to have some bums.”

Miller may have had his share of horses who have not performed to expectations, but he also has had his share of very talented runners. “I thought that Winter’s Tale was as good as I’ve had. You had to be around to understand that he had problems. Little accidents happened, but he was a good racehorse. I certainly thought that Fit to Fight was a very, very good horse. People say: `Well, you know, he didn’t beat much.’ But he won the Triple. He ran the Metropolitan in 1:34, he won the Suburban, and he won the Brooklyn, and he carried 129 pounds in the Brooklyn and won by an eighth of a mile (actually, 12 1/2 lengths). You know, good horses can do that; bad horses can’t.

©Suzanne Haslup

“Obviously I loved Java Gold. He was a star, in my opinion. He was a special horse. Other than the foot, he was beautifully sound‑‑he never bucked, and he never had an injection of any kind in his joints, and he was never fired or blistered. He was a rock‑hard, sound horse.” Indeed he was, as rock‑solid and sound as MacKenzie Miller was as a horseman.

Dr. Audrey R. Korotkin won two Eclipse Awards for WBAL Radio in Baltimore, became the first executive director of Triple Crown Productions in 1986, and—after a career change in the 1990s—now is the rabbi of Temple Beth Israel in Altoona, Pa.