Almost exactly 30 years ago, Thoroughbred Times Editor Mark Simon launched an ambitious book project that would profile the leading trainers of the second half of the 20th century. Don Clippinger, by then the former editor of the Thoroughbred Record, was given the assignment of editing the book and wrote the profile of W. Burling Cocks. Now the National Steeplechase Association’s communications director, Clippinger knew Cocks well from his time at the Philadelphia Inquirer and spent several days with him at Hermitage Farm in Unionville, Pa., in the summer of 1990. For a number of reasons, the book never was published, but condensations of several chapters appeared in the pages of Thoroughbred Times in the 1990s. The work that follows is the full chapter with only modest editing. Burley Cocks retired in 1993 and died at Hermitage on Feb. 8, 1998 at the age of 82. Barbara “Babs” Cocks died on Nov. 26, 2015 at the age of 96. MacKenzie Miller, who owned the race course where the Aiken Steeplechase is now located and trained the flat horses of Virginia steeplechase owner Paul Mellon, will be profiled in a subsequent chapter written by Audrey R. Korotkin.

Burley Cocks: A trainer of horses and horsemen

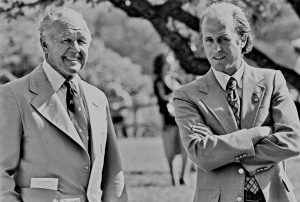

1975 at Rolling Rock. ©McCully

by Don Clippinger

The Belmont Park racing fan, in his early 30s and thus a bit younger than the average patron on a midweek afternoon in October of 1982, paused before a large-screen television on his way to cash his tickets. A few moments earlier, on one of those glorious autumn afternoons at Long Island’s western edge, Zaccio had humbled four rivals in the 59th running of the Temple Gwathmey Steeplechase Handicap. Ridden by young Ricky Hendriks, the two-time Eclipse Award champion had spotted his opponents–including two other stakes winners–a minimum of 13 pounds and still blew them off with ease, winning by 3 1/4 lengths.

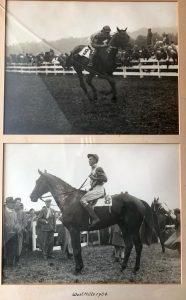

Zaccio and jockey Ricky Hendriks at the Temple Gwathmey. ©D’Orio

In Belmont’s winner’s circle, Mrs. Madeleine Huntington Murdock, better known as Bunny, had accepted the Temple Gwathmey Cup, entrusted to the winning owner for a year. At her side was W. Burling Cocks, arguably the best-respected and best-liked trainer of steeplechase horses in the last half of the 20th century and the person who had selected the *Lorenzaccio gelding as a yearling. It was Cocks—at the time, a steeplechase horseman for half a century—who had developed Zaccio into a three-time champion and who had nursed him back from accident and injury.

The trophy presentation was completed, and the race patron knew he would be cashing some relatively small tickets. Zaccio had gone off as the prohibitive 3-to-5 favorite, and the $2 win mutuel was worth only $3.20. Still, the patron expressed no dissatisfaction as he paused on Belmont’s first-floor grandstand and watched as Zaccio cruised to the lead and then suddenly burst away from his opponents in the stretch. The patron smiled as he turned to go collect his 60 cents on the dollar. “It’s like a gift,” he said to no one in particular.

Indeed it was a gift, a commanding performance by a champion at the top of his game. But Zaccio’s Temple Gwathmey victory, as well as many others, represented gifts of a different kind. To be sure, Zaccio was a talented racehorse, the best one that Burley Cocks ever trained, and he was installed in Thoroughbred racing’s Hall of Fame in 1990. But the most notable gift is the one that Cocks has for training horses. It is a gift that he has nurtured through seven different decades, starting on a bleak day in 1932 when he rode his first race (and was disqualified) and continuing into the century’s final decade.

He has won just about every American steeplechase race that is worth winning, and he preceded Zaccio into the Hall of Fame by five years. He has collected other awards, however, that speak more about the man’s character than his talents with horses. He received steeplechasing’s F. Ambrose Clark Award in 1973 for his contributions to the sport and the New York Turf Writers Association’s award for outstanding contributions to racing in 1982. In addition, he was honored with South Carolina’s Palmetto Award, with which the state’s governor designated him a “Palmetto Gentleman,” in 1985. Although he is based most of the year in Unionville, Pennsylvania, about 30 miles west of Philadelphia, he has spent each winter in South Carolina since the 1940s.

Those awards have been bestowed upon the mild-mannered Cocks not so much for the excellent horses that he has sent out from his Hermitage Farm, but for the top horsemen who have departed its gates and made their marks both over fences and on the main track. As much as he is a trainer of horses, his legacy most certainly will be that he has been an exemplary trainer of other horsemen. The dedication of his F. Ambrose Clark Award, noted in the 1973 edition of Steeplechasing in America, identified many who had come under his influence.

1980 at Rolling Rock. ©Lees

“While Burley has conditioned many top jumpers and encouraged a multitude of owners to test the waters of the infield sport, his greatest contribution to the world of steeplechasing is the way he has taught and encouraged a series of young men to follow in his footsteps, first as riders and eventually as trainers. Such men as Charlie Cushman, `Mike’ Freeman, Ronnie Houghton, Doug Small Jr., Jonathan Sheppard, and Mike Smithwick are typical of those who passed through the Cocks `school.’ Each has achieved a measure of success that speaks volumes for the value of the Cocks influence.”

Although some of those names are not known widely outside of the steeplechase world, they contain two Hall of Fame trainers in Smithwick and Sheppard, and Freeman trained the great Shuvee, a member of racing’s Hall of Fame.

The list was not meant to be in any way complete, though, and among those omitted were Louis C. `Paddy’ Neilson III and Charles C. Fenwick Jr., both champion jockeys over timber fences who now train steeplechase horses, particularly for the post-and-rail races. Neilson, who walked away from a career as a bond broker to train full-time in 1987, both trained and rode the 1989 Maryland Hunt Cup winner, Uncle Merlin. Fenwick, who trained Dogwood Stable’s steeplechase horses into the 1990s—including 1987 champion Inlander (GB)—rode Ben Nevis II to a victory in the 1980 Grand National at Aintree, England.

The 1973 listing also passed over a former Cocks rider and assistant trainer who had overseen the operation’s younger horses. When William H. Turner Jr. was ready to go on his own in 1966, Cocks put him together with the Hickory Tree Stable of clients James and Alice Mills. Subsequently, Billy Turner would hook up with Tayhill Stable and a rocket ship named Seattle Slew. Under Turner’s painstaking care, Slew became the first undefeated Triple Crown winner in 1977.

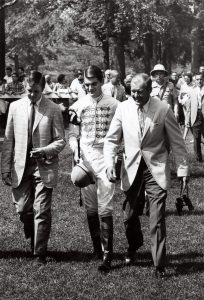

Tommy Skiffington ©Lees

The Cocks `school’ did not let out after this group of horsemen. Among the more recent graduates is Thomas Skiffington, a champion steeplechase jockey who has developed into one of New York’s leading trainers while concentrating on grass horses. Hendriks, who rode into the 1990s, was to follow Skiffington to New York.

As noted by Charles T. Colgan, executive vice president of the National Steeplechase Association, Cocks “was always willing to give them more than a leg up on a horse.” Indeed he was. “He imparted his knowledge willingly,” Neilson said. “He’s had a very positive impact on everyone who has been fortunate enough to come in contact with him.”

He also gave to his students a part of himself, something that only can be described as character. “One of the things he imparted to us was to be a gentleman and a sportsman,” Neilson said. “He taught us that the horse and the sport were more important than the monetary rewards.”

Certainly, both “gentleman” and “sportsman” ably describe Burley Cocks. But the grandfatherly appearance and the soft voice can be deceiving. Deep inside is the spirit of a true competitor—one who possesses sufficient commitment to earn a plaque on the wall at the National Museum of Racing in Saratoga Springs, New York. “Beneath that quiet exterior lies the heart of a lion, but a very nice lion,” Neilson said.

Cocks rose to the top of the game without the benefit of any owners who were committed to putting big money into steeplechase horses. But most of Cocks’s clients do not sign on for a few years or even a decade or two. With few exceptions, they are with him for a lifetime. Back in 1933, Cocks rode the first winner for Stephen C. Clark Jr. In 1990, Cocks was trying to persuade Clark—who raced the undefeated Hoist the Flag—to send one of his better grass horses over fences. “They’re friends,” Cocks said of his owners. “You always try to get your friends going, and that’s the fun of it.”

Also through the years, Cocks has never answered the siren call of the racetrack and a large flat-racing operation. Although he has trained stakes winners on the flat, Cocks has remained true to the country sport, to keeping the sport in the country, and to training in the country.

In the last years of the 20th century, the area around Unionville is still country. Housing developments were beginning to intrude upon the horse-oriented hamlet in the late 1980s, but much of the land to its west is still open–in large part due to the efforts of one of Cocks’ neighbors, Nancy Hannum, who continued the fox-hunting tradition established by her stepfather, W. Plunkett Stewart, both before and after World War II.

William Burling Cocks was born on March 15, 1915 in Old Westbury on Long Island in the open country east of New York. Unlike Pennsylvania’s Chester County, the area in that part of Long Island no longer is the country. But, before the Depression, Long Island was an area of estates large and small. “They were big places, great for fox-hunting and polo,” Cocks said.

Cocks was born into a world that gradually was ending its dependence on the horse and was turning to internal combustion. His family had deep and longstanding ties to the horse. In 1803, his great-grandfather, Townsend Cocks, imported *Messenger, the foundation sire of today’s Standardbred.

His family’s roots in Long Island extended back another two centuries, to the migration of the Quakers out of England. Peter Wright, an ancestor on his mother’s side, arrived in the early 1600s. The Cocks family arrived in Oyster Bay, Long Island from the Caribbean in 1670. Cocks’s father, William Willets Cocks, incorporated Old Westbury. Through marriage, the Cocks family also was related to the Hicks family, for whom Hicksville was named.

Cocks’ father loved the American West, and he had purchased a ranch in Maple Hill, Kansas, in the 1880s and raised horses there. Many of the ranch’s mares, Cocks noted, had bloodlines tracing back to *Messenger. William Willets Cocks was the road commissioner of North Hempstead and utilized his Kansas-bred horses unprofitably in the political job. He told his son that he paid out more than his annual salary to repair the equipment damaged by the horses.

The elder Cocks shared a love of the West and of politics with a friend from Oyster Bay named Theodore Roosevelt. The Rough Rider was elected as William McKinley’s vice president in 1900 and assumed the presidency when McKinley died of an anarchist’s bullet on September 14, 1901.

Roosevelt was a progressive Republican, and the party’s political bosses, upset over his determination to break up many of the nation’s industrial monopolies, referred to him as that “damned cowboy.” An aristocrat and a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Harvard University, Roosevelt could handle himself on a horse. In the living room of Hermitage Farm hangs a picture of Roosevelt jumping a post-and-rail fence with one of the elder Cocks’ Kansas-breds.

Beginning with Roosevelt’s own term as President in 1905, William Willets Cocks joined him in Washington as the U.S. representative from New York’s First District. Known as the “Quaker congressman,” the elder Cocks served three terms. When his friend broke from the Republicans and founded the Bull Moose Party in 1912, Cocks campaigned as the Bull Moose candidate and was defeated by Martin Littleton. His seat subsequently was won by Cocks’ his brother-in-law, Frederick C. Hicks.

Cocks was 53-years-old in 1915 when his second wife, Jessie Wright Cocks, bore him a son, who was named for William Burling, the boy’s great-uncle. From the start, he was surrounded by horses and a tolerant attitude that was not always the norm in the days before World War I.

Quakerism, more properly known as the Society of Friends, steadfastly espouses pacifism, and it was among the groups at the forefront of opposition within the United States to the Vietnam conflict in the 1960s and 1970s. But its members have worked just as steadfastly to improve living conditions of the underprivileged. William Willets Cocks was true to his faith; he would frequently offer a helping hand to immigrant families. “He gave them jobs and houses to live in in Westbury,” his son said.

Burley Cocks was in the saddle of his father’s stalwart Kansas-breds before he was in school, and he hunted over the vast Long Island estates beginning at age ten. Through the hunting field, he came to know James Maloney, who would become a trainer in New York. “His father ran Piping Rock Stables across the road from the Friends Academy,” Cocks said. “Jim was always a good friend. He was seven or eight years older than I was. They were good horsemen, and I always enjoyed schooling their horses. Jim was always interested in racing.”

So, too, was young Burley Cocks. He played some polo, “but I was too busy trying to ride racehorses.” He also attended the University of Virginia for a brief time. “I went in one door and out the other. They didn’t have any steeplechase horses down there,” Cocks said.

Steeplechasing, although an extraordinarily small corner of the Thoroughbred sport, seems to turn out an inordinately large number of successful trainers. Beyond those who have spent time at Hermitage Farm, others include Sidney Watters and Flint S. `Scotty’ Schulhofer. In earlier years, the list of top steeplechase trainers included Hall of Fame members Carroll Bassett, George H. “Pete” Bostwick, Thomas Hitchcock Sr., and J. Howard Lewis.

Cocks believes that they were the products of a total immersion in horsemanship, in which entire days, months, years, or lifetimes were committed to being with horses—riding them, caring for them, and often hunting them. When Cocks came into the sport in the early 1930s, almost all of the jockeys were amateurs who made their livings by training the horses that they rode. “Everyone was a horseman in those days. That was our whole lives,” he said.

The hunting field, from which steeplechase racing originally emerged, was no small part of the life. “That’s why we have fewer good horsemen now,” Cocks said. “When you were hunting, you would learn how much your horse could do. You tried to keep up with the hounds, and you had to know how much your horse had left and whether the horse was getting tired. Except for a few families, the young kids don’t hunt much anymore. Back then, you had so many people who taught their kids how to take care of a horse. They were such good horsemen.”

Through the years, Cocks has often hunted his steeplechase horses over the gently rolling landscape of southeastern Pennsylvania. “I used to hunt a lot of horses, particularly the post-and-rail horses. I hunted them all,” he said. “That’s where just about everyone makes their post-and-rail horses.”

Cocks was himself the product of total immersion in horsemanship—although his family would have preferred that he not become an amateur jockey, a “gentleman rider” as they were then known. For the son of a former congressman, a career astride a horse was perhaps not gentlemanly enough. “That wasn’t acceptable,” he said. “I probably shouldn’t have done it, but I don’t regret doing it.”

While still in his mid-teens, Cocks apprenticed with one of the nation’s leading steeplechase horsemen, F. Ambrose Clark, whose Broadhollow estate was located in Old Westbury. It was with Brose Clark that Cocks would take his degree in horsemanship.

Clark was one of America’s richest men, but he left the financial matters to his brother, Stephen, and devoted his life to his stable of approximately 30 steeplechase horses. “That’s all he cared about,” Cocks said. Clark was, in a word, an eccentric. He disdained the automobile and only used one when it was absolutely necessary. Until shortly before his death in 1964, he would be astride his Welsh coal pony, Bijou, at his home and at hunt meetings.

A man of a few, well-chosen words, he received the unwelcome suggestion from his doctor that he give up two of his dearest pleasures, champagne and strong Havana cigars. He responded by changing doctors. His horses lived in fine style—the Broadhollow stables sparkled with highly polished brass—and his guests also were well cared for. Following mid-morning races on the estate, Clark would be host to more than a hundred guests for a luncheon at which fine food and even finer champagne filled the tables.

Cocks rode his first race in 1932, during a period that could well be considered the golden age of American steeplechasing. The duPonts were major patrons of the sport, as were the Wideners, and the Mellon family was becoming involved in the jumping sport. In addition to Bostwick, who also apprenticed under Brose Clark, and Bassett, some of the other gentleman horsemen were Noel Laing, James E. Ryan, Raymond G. Woolfe, and Morris H. Dixon.

Cocks said that Bostwick, who had considerable experience on the flat, was the best steeplechase jockey he ever saw. “Laing was a good rider, and Bassett was, too,” he said. “Bobby Davis was a great stylist. He had beautiful hands. Pete Bostwick was tremendous. Laing and Bassett were bigger guys, but Pete was built more like a jockey. I tried to copy Bostwick, but he was too small.”

As a result, Cocks said, his style of riding was closest to that of his friend Noel Laing. Still, Cocks was not as large as some of today’s steeplechase jockeys. Although relatively tall at 5-foot-10, “in those days, I could do 130 pounds comfortably,” he said. The young Cocks was a natural, with soft hands and a good sense of pace. Paddy Neilson’s grandfather, Louis Neilson Sr., was a neighbor of the Cocks family in Old Westbury and said the teenager was the best rider he had ever seen.

But that first race on November 19, 1932 was an auspicious beginning. The race was the Willie Price Challenge Cup at the Meadow Brook Point-to-Point on the estates of Middleton S. Burrill and Daniel Underhill in Jericho, New York. The setting may sound genteel, but the conditions certainly were not. Burley Cocks was aboard a half-bred gelding named Carry On in a contest that was described as “a weird race, run in pouring rain and a southeast gale.” That description hardly did justice to the conditions, Cocks said. “It was one of those Long Island storms. You couldn’t see a thing. I followed the tracks of the horse that was leading. I went the way he did,” Cocks said.

The leader crossed the finish line first, and Carry On finished second. The only problem was that the winner had gone off course at the 12th fence, and Cocks had cut the same flag while tracking the leader. Both were disqualified.

His first victory came on April 22, 1933 under perfect conditions at the Meadow Brook-Smithtown Point-to-Point over the estate of Charles E. F. McCann in Oyster Bay, New York. Cocks rode Tom Adams, owned by Mrs. Robert Winthrop, to a 10-length victory over Pantheist in the 4 1/2-mile race over timber fences.

Those were “tin cup” races, run for the sport of it and a piece of silver. Cocks notched his first victory at a sanctioned racetrack on November 7, 1933 at United Hunts Association’s autumn meeting at Belmont Park. Cocks was aboard Greatorex, a five-year-old gelding trained by A. J. Davis, and the conditions rivaled those of Cocks’ first race a year earlier.

Greatorex had no opponents and scored in a walkover. But there was some dispute over how extensive this walkover would be. “That was a very embarrassing affair,” Cocks said. “It came up terrible mud. George Cassidy said he wanted me to jump the entire course. I said I’d fall off for sure. I jumped one fence and came back.”

Four days later, Cocks won the Homeland Purse at Virginia’s Middleburg Hunt Races aboard Sun Wrack, the first horse owned by Stephen Clark Jr., the nephew of trainer Brose Clark. The race’s footnotes provide an apt description of Cocks’ riding style: “Sun Wrack, receiving a well-judged ride, was rated off the early pace, then gradually made up ground in the last mile, jumped the last as a team with Our Friend, and went on to win by a neck in a driving finish.” The victory also marked one of Cocks’ first associations with horses containing *Wrack in their pedigrees.

Cocks ended 1933 with four victories, two second-place finishes, and nine thirds from 23 starts. In those days, the line score also included the types of races. Cocks had won one race over timber fences, two races over brush fences, none over hurdles, and one on the flat. Today, the distinction between brush and the smaller hurdles has been obliterated by the sport’s adoption of artificial fences, known as National Fences, which are a hybrid between the two types of obstacles.

His four victories were good enough for 19th place behind Carroll Bassett, who won 23 of his 70 starts. Bassett both rode and trained for Mrs. T. H. Somerville, the former Marion duPont. In later years known as Marion duPont Scott, the sister of William duPont Jr. played a major role in the sport until her death in 1983.

In the 1930s, American steeplechasing was significantly smaller than its counterparts in England and Ireland, but she went to one of the shrines of British jump racing, Aintree, and came away with a victory with her little chestnut, Battleship, in the 1938 Grand National. Earlier in the decade, she had tried the Grand National with Trouble Maker, winner of the 1932 Maryland Hunt Cup, and come away empty-handed.

“I learned from Trouble Maker’s effort over there,” she told Gerald Strine. I learned that a high-class horse was needed to win; that while those big English and Irish jumpers looked like the kind of horse you think a fat man would ride in the hunting field, they were misleading. Very misleading. They could turn it on. They would fool you with their speed.” But Battleship—referred to as the “pony stallion”—would not be fooled. Under young Bruce Hobbs, he threw his compact, 15.2-hand body over Aintree’s 30 towering fences and used his speed to catch favored Royal Danieli in the last stride.

It was the second victory of the decade for an American owner. In 1933, Kellsboro’ Jack had toured the Aintree course in a record 9 minutes and 28 seconds. The Irish-bred had been bought as a yearling by Brose Clark, who sold him to his wife for £1.

A 1934 win photo, courtesy of Barbara Vannote

In 1934, the victories began to pile up for the 19-year-old Cocks. Bassett again was the leading rider, but the young gentleman jockey from Old Westbury climbed into fifth place with 18 victories, 21 seconds, and seven thirds from 75 mounts. He won two races at the Rose Tree hunt meet in Media, Pennsylvania and scored in the Warrenton Hunt Cup, a Virginia timber race, aboard Gil Blas.

He rode Mrs. Tim Durrant’s St. Francis to a victory in the Great Long Island Hurdle Race at Cedarhurst, New York, and a month later, in June, turned the tables on St. Francis with Fairy Lore. A tough old dude, Fairy Lore had never won a race with anyone but Laing, his regular rider. But, for the featured race at Raceland, John R. Macomber’s estate in Framingham Center, Massachusetts, “the horse got in light in the handicap, and Laing couldn’t do the weight, Cocks said.

Just before the race, someone walked up to Cocks in the paddock and said, “Good luck, Noel. I hope you win.” Laing was standing nearby but said nothing. As Fairy Lore wheeled and propped on his way to the course, Cocks yelled to his friend: “Laing, go in and bet on this sucker. That’s a hunch. Maybe he’ll think I’m you, too.”

Cocks always has had a reputation for taming the toughest customers, but in this race the *Wrack gelding dragged them to the lead at the first fence, and they remained there to the wire, winning by six lengths over St. Francis.

Late in the season, Cocks won the $5,000 Foxhall Farm Challenge Cup, a timber race in Harford County, Maryland, aboard Indigo. The purse was big money in the midst of the Depression, but Cocks said he and his fellow riders enjoyed a good life without much money.

“In those days, it seemed the whole set-up was different,” he said. “You’d go to New Jersey for a week and spend some time there. Essex had two days, Wednesday and Saturday. Montpelier, in Virginia, was Friday. On Thursday evening, we’d drive to Montpelier and stay in a six-bed dorm room.” Marion duPont, the owner of historic Montpelier in Orange, Virginia, would stage her races on the grounds of the estate.

“It was great fun,” Cocks said. “To get back to New Jersey, Willie duPont would have his rail car waiting at Montpelier Station. It was two to a berth. I drew the top berth with a big guy, Paul Brown, and he slept on top of me all night. Those private rail cars were wonderful. They could latch onto any train they wanted.”

Still, the sport could be deadly. In the early 1930s, Cocks’s friend Temple Gwathmey—son of the man for whom the steeplechase stakes race was named—died in a spill. After his death, Gwathmey’s mother gave Cocks one of his horses, Hermitage. The horse had shown some promise as a three-year-old in 1929, but sustained an injury that compromised his career. “He was a bad-legged horse. He had bowed a couple of times,” Cocks said. I was just trying to hold his old legs together.”

As 1935 began, Cocks was poised to move toward the head of the riders’ standings. At Camden, South Carolina, he rode The Stag II to a victory for Richard King Mellon, chairman of Pittsburgh’s Mellon Bank.

He rolled through the spring. On May 4, Cocks rode Indigo to a victory in the Virginia Gold Cup, and Town and Country magazine noted in its June, 1935 issue that “the result was another runaway race for the Northwood Stable’s Indigo, guided with consistent competency by `Burley’ Cocks.”

Burley Cocks on Hermitage, as painted by I Wanamaker in 1940

Three days later, at the first day of Radnor Hunt’s eighth spring race meeting at Chesterbrook, Pennsylvania, Cocks proved that he had held Hermitage’s legs together in excellent order. Under his owner, Hermitage cruised to a 10-length victory in the Gardner Cassatt Challenge Cup.

The victory put the 20-year-old jockey into a tie with Bassett with nine wins for the season, and many more lay ahead of him. On May 13, he was to report to the Belmont Park barn of Thomas Hitchcock Sr. to ride a horse for him. But Cocks would never make the trip.

Radnor Hunt’s first race on May 11 was the Rocky Hill Plate, a mile on the flat, and Cocks was aboard File Away, a four-year-old filly. The weather was not cooperative. After several days of dry weather, “the ground had been hard and it had drizzled rain for about two hours before the race. It was greasy as hell,” Cocks told Peter Chew.

“Bassett was in front of me on Sable Muff and Sid Hirst was on the inside and Noel Laing was on the outside,” he said. The chart of the race noted that File Away, “showing good speed from the barrier, was improving her position when she fell going into the last turn.”

“She really filed me away,” Cocks said. “The ground sort of sloped away and the mare crossed her legs and slipped. I went down going into the turn, and then Bassett went down going out of the turn, but he wasn’t hurt. I fell on the rail, and they all galloped over top of me.”

Morris Dixon’s mount, Chade, apparently kicked Cocks in the right side of the forehead as the other jockeys scrambled to avoid the fallen rider. Well after the accident, Dixon jokingly called his protege a “hard-headed bugger,” Cocks recalled. “He knew he stepped on somebody, and the horse broke down.”

Immediately after the accident, however, no one was cracking jokes. Race officials were frantically trying to locate Cocks’ mother to obtain her permission for surgery. They did not find her, but they located Brose Clark at the Rockaway races on Long Island. “He said, `Get the best vets you can find and go ahead. I’ll take the responsibility’,” Cocks was told.

The fallen jockey also was fortunate that Dr. Hubley Owen, the Philadelphia Police Department’s surgeon and the father of rider Ned Owen, was at the races that day. Cocks was taken by ambulance to Chester County Hospital in West Chester, where Dr. Owen and Dr. Charles Kerwin spent two hours picking bone fragments from his skull. “That’s what saved me,” Cocks said. As the police surgeon, Dr. Owen “knew something about busted heads.”

He was in a coma for 19 days and was hospitalized for three months. From the day of the accident, Cocks had an indentation about the size of a silver dollar on the right side of his head, about two inches behind the hairline. Red Smith, the New York Times sports columnist, referred to him as “the trainer with a hole in his head.” He was told that he could never ride another race, and the young man with a hole in his head was smart enough to never ride in another race. He would, however, spend plenty of time in the saddle over the ensuing decades.

Cocks recuperated at his mother’s Long Island home for a year. Friends came by to see him, and so did the immigrant families that had been helped by his father. “You don’t know how many people feel about you that way,” he said.

He still owned Hermitage, who won the Mount Defiance Cup at the Essex Fox Hounds meeting in Far Hills, New Jersey on October 23, 1935. Anderson Fowler rode the gelding, who was trained by T. J. `Tommy’ Tault Jr., an old flat conditioner who was one of Cocks’ teachers in the fine art of horsemanship.

After his recuperation, Cocks tried the life of an advertising man in Manhattan. For someone who had already spent so much of his life outdoors, it was a doomed venture. He also spent portions of two years in the American West. Those were memorable times for Cocks, and perhaps most memorable was a pack-horse trip to Montana with some of his fellow jockeys in 1937. At one point during the trip, “we were camped by a trout stream. Andy Fowler was fishing from horseback.”

Well, at least Cocks remembered the good times and the camaraderie. Some others may not have. “We had one pack horse loaded with all of the liquor that he could carry, but that ran out,” Cocks said. “I didn’t drink, and I was designated to go get more liquor. I rode and led my horse over a mountain pass to get liquor. I rode hard, because everyone was dying. I covered 36 miles over trails in a day and a half. I got back and didn’t break a bottle.”

But one person was missing from the trip. “Laing was to come, but he had to check into the hospital,” Cocks said. During that hospital stay, it was discovered that Noel Laing was suffering from cancer. Before too long, Cocks and the other gentleman riders would lose their friend.

After his accident and recuperation, changes had to be made in Burley Cocks’ life, and many lay just ahead of him. But changes were occurring in the steeplechasing sport as well. In 1938, Paul Mellon—who eschewed the family’s banking business and settled in Middleburg, Virginia, where he cultivated fast horses and the fine arts—became the sport’s leading owner. The leading jockey was John Magee, a professional. The era of the gentleman jockey was rapidly coming to an end, and would be the exception rather than the rule by the end of World War II.

Long Island, the wide-open territory where he had roamed as a boy, hunted as a youth, and ridden races as a teenager, also was changing. Some of the changes struck very close to home. In 1939, the 70-acre family homestead along Jericho Turnpike was sold to satisfy tax liens. “We had to sell the property for practically nothing to pay the school taxes. If we had kept it another year, we would have gotten $4-million,” Cocks said.

When he incorporated Old Westbury, William Willets Cocks had retained three acres in the town’s center. “We couldn’t sell it,” his son said. The Cocks family was not alone in their plight when the tax man came calling in the latter years of the Depression. Many of the old estates were broken up, setting the stage for the wildfire suburbanization of western Long Island in the years immediately after World War II.

While he was still riding and during his recuperation, Cocks said he watched the best steeplechase horse he ever saw. That horse, Bushranger, raced in the colors of his breeder, Joseph E. Widener.

By *Stefan the Great and out of War Path, by Man o’ War, Bushranger sustained a fatal injury in a schooling accident in 1936 and was posthumously voted the year’s champion steeplechase horse. He won 11 of his 16 jumping races, including the 1936 Grand National Steeplechase Handicap at Belmont Park under a then-record 172 pounds and the Brook Steeplechase Handicap under 165 pounds that year.

“Howard Lewis trained him. He’d give him a run over the flat to get him ready to run. He’d run him over the old Aqueduct track, which was one of the slowest tracks around, and he’d run a mile in 1:37 or 1:38. Then he would come out and run three miles like it was nothing,” Cocks said. “He was something.”

Cocks said that *Stefan the Great, who was by The Tetrarch, sired many good jumpers, but he has all but disappeared from American bloodlines. Other major jumping lines also have faded away. “The only one still showing up is Man o’ War and Fair Play. That’s still there,” he said.

In 1937, Cocks received a call from Jim Ryan, who had the largest string of horses in Unionville. “He had to go abroad to buy horses. I came down here to Unionville and stayed while he was abroad and took his horses to Camden, South Carolina in the spring of 1938. I came back up with him as assistant trainer,” Cocks said.

Ryan and another Eastern Pennsylvania horseman, Morris Dixon, would become major influences on Cocks in the years before he began training a public stable at the end of World War II. “Jim Ryan was a good jockey, and he trained a lot of the horses he rode. He bought a lot of horses and put all of the Mellons into the business,” Cocks said. “He was an all-round sharp horseman, and the best raconteur there ever was. He was full of stories. He was a very amusing fellow.”

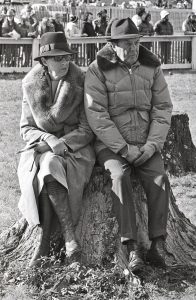

Burley and Babs at Foxfield. ©Birkenstock

While hunting near Rose Tree in 1938, Cocks met Barbara `Babs’ Lucas, an accomplished horsewoman in her own right who both showed and hunted. Soon they were dating; soon, they wanted to get married. But Babs’s father, G. Brinton Lucas of Midstream Farm in Paoli, insisted that his prospective son-in-law have steady work. “He was smart, I guess,” Cocks said.

While the marriage plans were at an impasse, Plunkett Stewart received a letter from Rachel Ingalls. “She knew something about hunting, breeding, and racing and wanted to set up an operation in Hot Springs, Virginia,” Cocks said. He was hired, and Burley Cocks married Babs Lucas in October of 1940. Their first child, Susan, was born in 1942, and three other children followed. But Babs Cocks did not retire to the kitchen and the nursery. “She was the best lightweight exercise rider I had. She raised these kids, and she had some rough falls, too,” Cocks said shortly before he and Babs celebrated their golden wedding anniversary.

Mrs. Ingall’s husband, Fay Ingalls, owned a resort hotel in Hot Springs, but by 1942 the hotel had some unexpected and unwanted guests. Cocks said members of the Japanese diplomatic corps, detained after the attack on Pearl Harbor, were housed at Ingalls’s hotel on the order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

On the whole, the trainer said, the Japanese did not avail themselves of the mountain air, particularly in light of the political climate. Fearful that some Virginia patriots would shoot at them if they chose to stroll the grounds, the diplomats generally stayed indoors throughout the war. In fact, one of them panicked when he found himself momentarily locked out of hotel and out in the open.

Shortly after their marriage, Mrs. Ingalls named a weanling filly after Babs and another after Burley. Beaubabs, by *Gino and out of Beauflower, by Sun Beau, did not race, but she proved to be a foundation mare of extraordinarily durable jumpers. Among her progeny, it was not unusual to find horses with 40 or more career starts. Fiddling Star, a great-grandson of Beaubabs, made 164 starts and set track records at five and 5 1/2 furlongs.

Cocks took out his first trainer’s license in 1941 and first made the list of top trainers in 1944, when his eight winners put him in eighth place behind Jim Ryan. The war nearly shut down steeplechasing—in 1944, only 235 horses started in 184 races—and then F. D. R. shut down racing totally. “I was sitting on horses in South Carolina, waiting to run, when Roosevelt put in the ban on racing till the end of the war,” Cocks said.

It was then that Cocks received an enticing offer. Plunkett Stewart, master of the Cheshire Hounds in Unionville, was anticipating the end of the war as Allied troops pushed beyond their Normandy beachhead toward the Rhine. Cocks agreed to work for a year re-establishing the hunt. “I parked some horses with Morris Dixon and some other friends that I knew I’d be able to get them back from,” Cocks said.

The Stewarts had a racing background. In Mrs. Stewart’s name, they had won the 1938 Belmont Stakes with their homebred Pasteurize. But his first love was the hunting field, and he owned most of it. “He owned most of the ground around here,” Cocks said.

One of his properties was a dairy farm with approximately 400 acres. Cocks worked out a deal to buy 110 acres, including an 18th-century stone farm house, a stalwart barn, and a tenant house that sat near the farm’s entrance. “I could have had as much land as I wanted, but I thought 110 acres was enough,” Cocks said. “I wanted to keep enough money to fix up the barn and the house.”

Cheshire was two-horse country in those days—one horse for the morning and another for the afternoon—and the season extended from September through mid-March. “Sometimes, you’d go a little after that. It was great fun, but it was tough in a way. You had more fences then. It was terrific. The more jumping, the better. But we’d be out from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., often in sleet and cold. By the time you came in, it would be dark and cold,” Cocks said. It proved to be too taxing. “I was doing too much riding, and it was bothering my head,” he said.

After a year with Cheshire, Cocks collected the horses that he had parked with friends and began training a public stable out of Hermitage Farm. More than four decades later, he was still training a public stable at Hermitage.

With the end of the war, racing resumed, and the riders returned from military service or their wartime jobs. Horses that were ready to run were in short supply, but Cocks had several of them in his converted dairy barn. As a result, Hermitage became a magnet for many of the leading riders, and the growing Cocks family housed them in the old tenant house, which was nicknamed `Lower Slobovia.’

Riding talent abounded in Lower Slobovia. Among the tenants were Mike and A. P. `Paddy’ Smithwick, Mike Freeman, and Charles Cushman. “We had a lot of lesser lights, too. One of the greatest things was that they turned out to be great horsemen,” Cocks said. “I was very lucky to get guys like that, but I was the only game in town. I had all of the amateurs here. Cush had a little money, and Mike had a little money. I didn’t have anything to pay them. We did feed them and give them a place to stay, but that was it.”

Lower Slobovia, as the name implies, was not exactly luxury quarters. “In those days, it was a little shabby,” Mikey Smithwick said. “We worked hard and had a good time. They treated us well.”

From the very beginning of his training career, Cocks provided more than a leg up for his riders. “He was the world’s best. He could do anything with a horse,” said Smithwick, who was 18-years-old when he took up residence in Lower Slobovia. “He would show you how to do something, and then he would come back a week or so later and see how you were doing.”

Also at a very early point, Cocks’s philosophy of horsemanship already was well formed. Of his riders, he said: “You try to teach them a little horse sense. They all had some. Every horse, treat them like a good horse, because you never know. Always give them a break. That’s so important, not to make the wrong move around a horse early on. Because a bad move can ruin them.”

His former riders say that he consistently projected a positive attitude toward the horses. “He always looked for the best in a horse,” said Jonathan Sheppard, the all-time leading steeplechase trainer who was inducted into racing’s Hall of Fame in 1990. “Every horse that came to Burley’s barn was a potential champion till he ran a few times. You become mentally geared toward giving the horse a chance.”

In a relatively few years, Cocks and his Lower Slobovia crew of amateurs were making their mark on the hunt-racing scene. In 1947, Cocks was sixth on the list of leading trainers, tied with Morris Dixon and Sid Watters with 10 victories.

The following year, he saddled 21 winners and tied with Sid Watters and Arthur White for the races-won title. As had occurred in 1947, Cocks did not hit the money-won list. He was winning in the country, and collecting country purses as well as tin cups.

In 1948, Cocks saddled nine winners for Alvin Untermeyer, a Connecticut sportsman, and Rachel Ingalls’s Extra set a course-record in a hurdle race at Saratoga. “He was bred in Hot Springs. He was extra, too. He was by this young horse, Black Mat, who they didn’t cut. His dam was an old *Wrack mare, Pop Gun,” Cocks said. Subsequently, Extra sustained a deep cut on a knee when he got loose and ran into a guy wire. Cocks purchased him from Mrs. Ingalls and gave him plenty of time. He came back to form in 1950, winning two races and finishing second in the Riddle Cup at Rose Tree. He also won two races in 1951 for Cocks.

Also in 1948, Cocks notched his first victory in a major race when Edward Q. McVitty’s Peterski was placed first in the Maryland Hunt Cup. Carolina finished first, but Mikey Smithwick noticed that the mare had jumped the eighth fence twice rather than an adjacent fence and did not ask Peterski to make a run at her. He finished second easily and moved up to the winner’s spot.

McVitty was from Long Island and, like Brose Clark, was something of an eccentric. “He was big on breeding racehorses and dressage horses,” Cocks said. “He had a hell of a time with trainers. He kept a book of all the mistakes his trainers made. But I got along with him all right.”

McVitty was a believer in jumping bloodlines, particularly those of *Wrack and Tourbillon. Cocks, who always liked the *Wrack horses, listened to his owner at length about the bloodlines developed by Marcel Boussac between the wars. “McVitty was a great believer in Tourbillon, and that’s what started me on it. They were all great jumpers and they had wonderful temperaments,” Cocks said. “Boussac inbred that horse tremendously without deterioration.”

Although McVitty’s horses never gained much recognition, Cocks said, “he sure knew what he was doing. He crossed certain lines, and he told you what the horse was going to be, and it worked out that way. He and Willie duPont would get to arguing. Ed would say, `Willie, why don’t you shut up about breeding horses.’ Willie would say, `When you’ve bred as many stakes winners as I have, then I’ll listen to you.’ He did win some pretty good jumping races at the tracks with them. They were useful horses.”

Cocks said that McVitty even could forecast a foal’s color. “He’d know the color of all these horses on their dam’s side. He’d breed a horse, and he could tell you what his temperament was going to be. He couldn’t tell you how good of a racehorse he was going to be. He would go through it and certain colors would mean something with him. Everyone would think he was nuts. But he bred some pretty good horses.”

McVitty’s selectivity was one of the factors missing in American breeding through the boom—and the overproduction that resulted—in the 1980s, Cocks said. Hardly no one breeds for jumping any longer, the strongest jumping lines have died out, and the American-bred horses that find their way into steeplechasing are not correct and therefore are likely to be unsound. Often, they will be cripples before they are sent over fences, and the steeplechase trainer must do his or her best to patch up the injuries and work daily to keep the horse sound. “Things are getting so expensive that the horses you get to jump all have had something wrong with them,” he said. “They’ve been tried, gone wrong, and then you have to patch them up. It’s a rough job.”

As a consequence, Cocks said, the horses that he has seen in the later years of the century are not of the same quality as those when he first began training. “The horses aren’t too much faster. Horses seem like they bleed a little more, there’s not as much bone, and they don’t seem to be as sound. They’re not as tough, and they don’t heal up as well,” he said.

“I think the soundness goes into breeding. They’re breeding such bad horses. They’re not breeding selectively, and no one goes to the trouble of looking at a horse they’re going to breed to or comparing him confirmation-wise to the mare they’re going to breed to or looking at any of the ailments they’ve had. We’re breeding bleeders and crooked-legged horses, horses that are not at all correct, rather than being selective. I think during times when the yearling market got so high, people were breeding anything and sticking them in sales all over the place.”

Peterski, a son of Petee-Wrack and thus a grandson of *Wrack, stood at Hermitage and did not distinguish himself from his limited opportunities. He had only 26 named foals in nine crops. One of his offspring was another Hermitage, named after Cocks’ first winner, but he did not perform as well as his namesake.

The 1948 edition of Steeplechasing in America noted the virtual end of amateurism in the sport. “The only weak timber in the steeplechase structure as a whole was in the amateur riding division. For the past decade, the ranks have been thinning in an alarming manner, and 1948 offered no solution to the problem.” With the exception of some timber jockeys who perpetuated the tradition—riders such as Charles Fenwick Jr., Paddy Neilson, Clinton Pitts Jr., and lawyer-brothers Jock and Buzzy Hannum (Mrs. Plunkett Stewart’s grandchildren)—there would be no solution.

By 1949, the crew of amateur riders had been joined by Eugene Weymouth, who was the son of one of Cocks’ owners, George Weymouth. Weymouth was an unlikely-looking steeplechase jockey at 6-foot-4, but he rode in many major races–including the Grand National at Aintree–and won the Maryland Hunt Cup in 1957 aboard Ned’s Flying. A trainer in later years, Weymouth also played a role, albeit an unfortunate one, in Cocks’ second straight victory in the Maryland Hunt Cup, America’s most prestigious race over timber fences.

Weymouth had the mount on McVitty’s homebred Cormac, who was showing promise of being an outstanding timber horse. “He was just some kind of horse when he got sound and right. He won three races and I ran him in the Maryland Hunt Cup, and it looked like he was going to win that. He looked like he had Pine Pep beat going to the second to last fence,” Cocks said.

Pine Pep, 1950 Maryland Hunt Cup.

Pine Pep, also trained by Cocks and ridden by Mikey Smithwick, was not making any headway until Cormac jumped the fence and landed on a broken beer bottle. “They used to fill the ditches on the road with stuff, and I guess an old broken beer bottle got in there. It was sticking up and it cut him,” Cocks said. The glass shard severed all of the tendons except the inside suspensory in one of Cormac’s forelegs. Pine Pep, owned by Mrs. William J. Clothier, went on to win by 12 lengths over Mister Mars.

Cormac was retired to stud and sired some useful horses, Cocks said. Pine Pep, who was by Petee-Wrack and out of Red Queen, by Mad Hatter, would win two more runnings of the Hunt Cup, in 1950 and, after bowing a tendon, in 1952.

Pine Pep was only one of Cocks’ winners in 1949. Under Smithwick, Alan M. Hirsch’s Swiggle set a Delaware Park mark for 1 3/4 miles over hurdles. By the end of the season, Cocks runners had accounted for 32 victories, placing him at the top of the trainers list in races-won. Again, though, he did not make the list of money-winning trainers.

But that situation would change in 1950, when he slipped to third on the races-won list but ranked sixth on the earnings tally. He continued to train for Rachel Ingalls, who sent him a chestnut filly out of Beaubabs. By Milkman, she was named Bab’s Whey, and she was no larger than a milk-cart pony.

“She was a very sound animal and trained real well as a baby. In the spring of her three-year-old year, she ran at Havre de Grace in an open maiden race. She won easily going three-quarters of a mile. She won again on the flat, and she won a lot of races over fences,” Cocks said.

“I remember when she won a maiden race at Delaware Park over the big brush fences. She looked like a foal running up with these two big horses, and she hung one on them right at the wire.”

Bab’s Whey also could handle the big brush fences at the Rolling Rock Races near Ligonier, a Mellon preserve about 50 miles east of Pittsburgh. In 1952, she finished second to Monkey Wrench in the International Gold Cup Handicap over the big fences.

Ligonier also was the scene of one of Cocks’ notable training feats, in which he won four races with two horses within four days in October 1956. Many of Rolling Rock’s races were named for small communities at the base of Laurel Mountain, and Cocks ended up winning practically the entire neighborhood.

Burley Cocks, courtesy of Barbara Vannote

First, he sent out *Evian to win the $1,500 Rector Purse, a two-mile race over hurdles, on Rolling Rock’s Wednesday program. Then, he saddled Dancing Beacon, who was owned by Mrs. G. P. Greenhalgh Jr., for a victory in the Ligonier Purse, a flat race. “I had to do something with him, because I couldn’t work him up there,” Cocks said.

Both horses rolled back into Saturday’s program and emerged with victories. *Evian took the $2,500 Laughlintown Purse, another two-mile race over hurdles. Dancing Beacon, after the tune-up on the flat, scored in the Western Pennsylvania Hunt Cup, a timber race.

But the streak was not over. Within three weeks, Dancing Beacon had won again, in the Monmouth County Hunt Cup, a three-mile timber race at Red Bank, New Jersey. *Evian, who was owned by Mrs. Vern Cardy, won the Noel Laing Steeplechase Handicap by six lengths on November 10 at Montpelier. “Noel being a great friend of mine, I always enjoyed winning that race,” Cocks said. Over the years, the Laing provided plenty of enjoyment. Going into the last decade of the century, he had won 11 of them, and his owners gave him a replica of the race’s trophy for a Christmas gift once.

With *Evian, Cocks tapped into the bloodlines of H. H. the Aga Khan. By Tehran and out of Queen of Simla, by *Blenheim II, the gelding was purchased by Tim Durrant from a dealer in Ireland. Durrant did not put much money down on the horse and shipped him to the United States, where he promptly smashed a hock while schooling over fences at Belmont Park.

Cocks acquired the horse and took him home to Unionville, where he took him across the road—literally—to the New Bolton Center, the large-animal clinic of the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine and its eminent surgeon, Dr. Jacques Jenny. The veterinarian put his patient on the table and removed seven bone chips from the hock. “I gave him a little over a year. He came back, and he was fine,” Cocks said. He also paid off the Irish bloodstock agent and sold him to Cardy.

Beginning in 1957, the students began to pass up the professor in the trainer standings. Heading the earnings list was Mikey Smithwick, who would head the money-won category for a record 12 times. His mark would fall to Sheppard, who headed the list beginning in 1973 and who looked to be ready to advance his record into the 1990s.

Cocks did not object their success; in some ways, he put them on the road. When the English-born horseman was ready to strike out on his own in the mid-1960s, “I told Sheppard, you ought to go to work on George Strawbridge right now.” Sheppard did, and George Strawbridge Jr.’s Augustin Stables became the leading money-earning stable in the history of the sport.

Saratoga paddock with jockey Doug Small. ©NSA Archives

Still, Cocks was consistently among the top 20 trainers in both victories and earnings through the 1950s and 1960s. He took in a new group of riders that included Sheppard, Paddy Neilson, Doug Small Jr., Billy Turner, and his own son, William `Winky’ Cocks.

“We took a group of wild guys,” Cocks said “Turner, he was the worst house-broke kid. He took wet towels and shut them up in a drawer. You never saw such mold.”

Nor have many people undergone a growth spurt like the one that hit Turner, who added six inches in 18 months. Steeplechase jockeys always have had bizarre methods of losing weight—such as driving to a racetrack in 90-degree weather with all of the windows closed and the car’s heater going full throttle. But Turner took a page from the past and had himself buried in the manure pile.

He needed to lose 17 pounds to ride a filly at Fair Hill, Maryland, and he had to do his reducing on a day that was not particularly warm. He wrapped himself in a plastic sheet, then had his co-workers bury him in the muck pile. They were kind enough to put a cardboard box over his head to ward off flies—and then promptly forgot about him. By the time Turner had had enough of his reducing regimen, he was too weak to dig himself out of the muck. At feeding time in the afternoon, “Burley went out and said, `Who left that paper box on the muck pile?’ ” Turner recalled. By the time he was freed from his odorous imprisonment, Turner was barely conscious. But he had lost 19 pounds.

Turner remembered Cocks as a horseman without peer. “He used to come out on any old racehorse that needed the experience of being around other horses. He’d sit on them very quietly and jump every fence. He was a phenomenal, phenomenal rider. He had a natural seat and wonderful, soft hands,” Turner said.

He also had a soft touch for the toughest of customers. “They were the green horses, the ones no one wanted or could handle. He’d ride them off, and they’d go easy,” Turner said. “You knew it could be done; so all you had to do was do it. And when you did ride them, you found out how tough they were.”

Cocks also had the touch for horses that had, for one reason or another, not attained their potential. He said he considered the best training task of his career was Mr. Steu, who was owned by Milton Ritzenberg. “That was one people would know. There are a lot of other horses that just won some small hunt-meet races,” Cocks said.

When Mr. Steu arrived at Hermitage in the early 1960s, the *Kingsway II gelding was running for a cheap tag at Charles Town—and still not doing well. In 1963, he earned only $1,250 in seven starts.

But Cocks changed that. “We got to schooling him and fooling around and ran him on the flat, on the grass,” Cocks said. “The thing about him was that he had trouble with his hind end somewhat. I think that keeping him completely off the dirt and just on the grass helped him as much as anything. That’s the way with most of them. They have something funny, but you change the curriculum and they get sound and they’re all right. There’s a lot of luck in it, too. He turned out to be a good, useful horse.”

Indeed he did. Mr. Steu finished second in Pimlico Race Course’s Dixie Handicap in 1963 and won the track’s Riggs Handicap the following year. Also in 1964, Mr. Steu finished second in a division of the Wilwyn Handicap and third in the Laurel Turf Cup Handicap. By his death in 1966, as a result of a fire in the Bellevue Training Center in Delaware, he had earned $84,171, most of it while under Cocks’ care.

Mr. Steu was one of the horses that seemed to benefit from a van ride. “He’d always run well with a ship. We’d drive him around for a half-hour or so in the van,” Cocks said. Another horse who benefitted from shipping was Jeff (Chi), who set a five-furlong track record at Delaware Park in 1984 and a turf-course record there at about five furlongs in 1988. “It always helped him. He was an arthritic, sore-going horse. He’d perk up, and he’d get off the van looking like he’d had a good treatment,” Cocks said. “A lot of horses wouldn’t run worth a damn unless they shipped in a van for a couple of hours. It was like they were on a vibrator, and they’d get as sound as a bell. They would run a lot better than they would if you warmed them up on the track; it wasn’t the same.”

With Doug Small Jr. riding many of the stable’s better horses, Cocks rocketed to the top of the standings in 1965, taking the title for most victories with 36 and trailing only Smithwick in earnings with $133,326. The trainer’s roster of owners also was filling. In addition to Ritzenberg and Mrs. Ingalls, he now was training for Unionville neighbors Miles and Joy Valentine, Lady John Thouron, and Mrs. Joseph Walker Jr., who was best known by her nickname, Avie.

Cocks won a race that year with Mrs. Ingall’s Vigorous Wheys, whose dam was Bab’s Whey and whose grandam was Beaubabs. He also began to utilize horses that had been imported from South America specifically for steeplechasing. Most of them were spotted by Jack Weipert or, in later years, Charlie Cushman. Golpista (Arg), racing in the colors of E. S. Voss, won Belmont’s Meadow Brook Hurdle Handicap as well as three lesser steeplechase features in 1965. Two years later, he won the Grand National Steeplechase Handicap.

For Lady Thouron, Cocks sent out Susto (Chi), winner of the New York Turf Writers Steeplechase Handicap in 1965 and Belmont’s International Steeplechase Handicap the following year. Susto, who set a course record in the Turf Writers and equaled one at Aqueduct, was unofficially designated as 1965’s champion older hurdler.

“Jack Weipert found him for the Thourons. He had pretty good form down there. He could run, and he was a hell of a jumper,” Cocks said “He broke down, and I gave him a year off. A year to the day, he won on opening day at Saratoga. He was a very sound horse, because he did a lot of racing. You could always count on him.”

In the early 1970s, *Lucky Boy III raced in the heart-studded colors of the Valentines and won the 1973 editions of the Noel Laing and the Colonial Cup International Steeplechase Handicap. Cocks continued the importations through the 1980s, including such horses as Tostadero (Chi) for Elizabeth “Betty” Moran’s Brushwood Stable, another longtime client.

The South American horses offered many advantages, Cocks said. “We’re trying to get a horse that hasn’t been raced to death and has shown something and has run maybe only two or three times. You get them after they’ve been tried a bit as three-year-olds, but they haven’t run a great deal. They seem to be tougher and stronger. Argentina has some really well-bred horses. You can go down there and still get some of the good, old jumping blood. Up here, it’s all bred out. You can’t get hold of it. There, you get some of the blood going back to the Hyperion horses. Congreve (Arg), that was a good jumping line. They were all pretty well-balanced horses.”

It is the balance, he said, that is most important in selecting a steeplechase prospect. “A well-balanced horse can do anything,” he said. “You want some brains, and you want some substance, size, and conformation. You want a good, laid-back front shoulder and a horse that has good use of his front end.”

Horses jump naturally, “but others adapt to it quicker than others,” he said. “Whether it’s brains, I don’t know. They get sense when they go to jumping. They rap a couple of those timber fences hard, and they change their outlook on a lot of things. Most of them come to enjoy it.”

In addition to a one-mile Fibar wood-chip gallop, which Cocks allows his fellow Chester County trainers to use during periods of hard ground, Hermitage has a schooling fence in the large, gently sloping field where the horses are galloped. But the early education takes place in a quiet, shaded portion of the farm, where the newcomers get their first lessons by jumping over logs lying on the ground.

“Logs are the best to start a horse, because it’s very solid and they can’t see through it. It seems more natural to jump those things,” Cocks said “They give them the basic idea that they have to jump. You give them those things to begin with to respect a fence and not take too many chances with it. That’s why we always school over solid fences, logs particularly, and they seem to jump them well. They shake them up if they hit them and they get a little idea of what they’re doing. They forget it after they get fit and running, but then you trot them over some logs, and it helps them again. You give them a refresher course once and a while.”

Cocks pulled down his second consecutive Turf Writers victory in 1966 with Spooky Joe, a Ritzenberg homebred who was the unofficial leading older hurdler that year. “That’s where he got his name, he was so damned spooky. They shipped him down to me in Camden, and they had to put ropes on him to pull him into the van, and we had to put ropes on him to pull him out of the van. He settled after he was eight or nine. He was always fine jumping,” Cocks said.

In 1969, Cocks surpassed $1-million total earnings, and the sport appeared to be in good health. But, with the rise of off-track betting in New York, the game that had been known as the “infield sport” was banished from Aqueduct’s infield, almost abolished at Belmont, and was curtailed at Saratoga. In 1970, when Aqueduct had 20 jumping races and had Belmont had 53, steeplechase purses totaled $1,350,558. By 1975, when no jump races were staged at either of the metropolitan New York tracks, purses plummeted to $741,295, with only $167,800 of that total coming from Saratoga’s 16 races.

“That was rough, because over a few years it knocked us out of a couple of million dollars in purses. We still had the hunt meets, but there wasn’t much money,” Cocks said. He places the major-track pullback not only on OTB, but on pari-mutuel wagering generally. “When the pari-mutuels came in, the hunt meets didn’t last long because people didn’t bet on the jumping horses. The biggest difference that occurred in my lifetime was when pari-mutuel racing came in, and it went in the hands of politicians. We had a long time when people in the commissions and such didn’t know one end of a horse from another.”

Cocks also places some of the blame specifically on Alfred G. Vanderbilt, who became chairman of the New York Racing Association in November 1971. “What didn’t help us any was Alfred Vanderbilt. Every track he took over, jumping quit. He did it at Pimlico, and then he took over Belmont and it quit, too. He just didn’t like it. He was no help at all. He’s gotten a better attitude on that as he’s gotten older,” Cocks said.

Through the 1980s, steeplechasing underwent a renaissance in both style and substance. The sport returned to its roots in the country, and the money became very good. By 1990, total purses were surpassing $3-million. “My contention all that time was that the hunt meetings were the proper locations for jumping, and corporate sponsorship would make a go of it,” Cocks said. “People got to working on it and did it, and it’s been terrific. That’s where this game really belongs. It’s a country sport, as it is in England. But it was hard to get that money going. But they did it.”

Through the 1970s, while the sport struggled to regain its footing, Cocks had some nice horses, including several bred by the Valentines. One of the last people to breed specifically for jumping, the Valentines stood the stallion *Mystic II, a French-bred horse who was owned by C. Mahlon Kline, a founder of the Smith, Kline & French pharmaceutical company and Miles Valentine’s uncle. Trained by Morris Dixon, *Mystic II won the 1959 Fall Highweight Handicap and Westchester Stakes.

He also represented some of the best jumping lines. On the top, he had Relic, a grandson of Man o’ War; on the bottom, his dam was Tosca, a daughter of Tourbillon. And, Cocks said, “he could jump like hell.” So, too, could his offspring. Soothsayer, bred and owned by Marion duPont Scott, was the Daily Racing Form‘s steeplechase champion in 1972, and the filly Life’s Illusion was the Eclipse Award winner in 1975 for owner Virginia G. Van Alen.

*Mystic II also was the sire of Arthur O. Choate Jr.’s Turtle Head, who Cocks believes was the most-underrated horse he ever trained. He did have talent, winning the Samuel K. Martin Memorial Steeplechase at Far Hills in 1984 and the Metcalf Memorial Steeplechase Cup Handicap two years later at Red Bank. He won eight of his 22 starts and nearly $100,000, which is a lot of money for a steeplechase horse. But he also was his own worst enemy.

“He was such a wild running dude, and I could hardly ever get him under control. He was just unbelievable,” Cocks said. “He would just hum. In the first Breeders’ Cup, he cut it out and finished seventh. I mean, he was doing some running and jumping. You couldn’t hold him until he ran out of gas.” In the 1986 Breeders’ Cup Steeplechase at Fair Hill, Turtle Head set the pace through the first 12 fences before his tank was empty and Census, the winner, caught him. Still, Turtle Head was not disgraced; he finished less than 13 lengths behind Census.

Another underrated *Mystic II was Babamist, who raced for the Valentines. A horse who traced back to Beaubabs through her daughter Babadana, Babamist won four of his five starts in 1973 before an injury effectively ended his career. “He won four straight over jumps, and I was running him in the Midsummer Steeplechase Handicap at Monmouth. He stood off a little too far at the fence in front of the stands—the fences were little boxes filled with brush—and he landed in the box. His hind legs stuck, and he cut his tendon in two,” Cocks said. “He was another one who didn’t live up to his potential.”

The Valentines at Montpelier. ©Lees

The Valentines certainly bred many who lived up to their potential. Tan Jay, the sport’s leading juvenile in 1975, won the 1979 Grand National Steeplechase Handicap at Foxfield, Virginia. Their top producer was Pocosaba, a mare who, while racing for Pete Bostwick, had won the 1963 Black Helen Handicap at Hialeah Park.

For the Valentines and trainer Cocks, she produced three major winners–Conesaba, Jacasaba, and Down First. In 1974, Conesaba (by Conestoga) won Garden State Park’s Cavalcade Handicap and a division of Pimlico’s Woodlawn Stakes. The eldest, Jacasaba (by Jacinto) took the 1977 Indian River Steeplechase Handicap at Delaware Park, defeating champion Cafe Prince, a subsequent Hall of Fame member, and setting a new course record. Down First, the youngest and by First Landing, won the 1979 Temple Gwathmey and Foxfield’s Grand National the following year.

Steeplechasing’s resurgence through the 1980s was assisted in no small part by the emergence of two superstars who, in succession, dominated the game for seven years. Zaccio, the best horse that Burley Cocks ever trained, won Eclipse Awards from 1980 through 1982. Flatterer, trained by co-owner and co-breeder Jonathan Sheppard, picked up the torch and carried it through 1986. Cocks considers Sheppard’s work with Flatterer to be the best training job by another horseman that he ever observed.

Zaccio was practically an accidental purchase by Cocks at the 1977 Saratoga sale. “I always look at the yearlings, just for the hell of it. I was looking for the Valentines,” he said. The chestnut colt by *Lorenzaccio was in a corner stall where Cocks saw him every time he went to make a phone call. It was almost as though this youngster was calling to him. “I went back and back and I couldn’t find anything wrong with him. He had good front legs and feet, and he was the soundest horse I had seen in a long time,” Cocks said. “I couldn’t resist him.” The Valentines bought him for $25,000.

In addition to the looks, he had the breeding. *Lorenzaccio traced back through three generations to Djebel and thus to Tourbillon. The yearling was out of Delray Dancer, by Chateaugay. “The Chateaugays could jump like hell,” Cocks said. She also was inbred, 3×3, to Polynesian, the 1945 Preakness Stakes winner who had been trained by Morris Dixon.

Zaccio was broken at Hermitage, and his disposition matched his looks. “He was as nice a horse as you’d ever want to be around. He was a very willing horse. He always enjoyed his work,” Cocks said.

Before Zaccio’s first start, Miles Valentine died, and his racehorses were dispersed at auction. But Cocks had lined up a bidder for the horse, and he was purchased for $22,000 by Bunny and Lewis Murdock in 1978. Unraced at two, he made his first career start on March 31, 1979 in a seven-furlong flat race at the Carolina Cup Camden, South Carolina. Under Tom Skiffington, he made a powerful move to draw into contention but hung through the stretch and finished third to Cheviot.

Delaware Park 1979, with jockey Richard McWade. ©Sheppard

Richard McWade was in the saddle for Zaccio’s next start, another seven-furlong flat race at Southern Pines, North Carolina on April 14, and “Zac” won by 2 1/2 lengths in hand. Two weeks later, Cocks stretched him out to a mile and, again ridden by McWade, he won by a length over Cheviot.

Zaccio now was ready to go over fences, but his first outing at Foxfield in Virginia very nearly was a disaster. While racing near the lead, Zaccio fell with McWade and ran off. “When I ran him at three, he was so precocious. He was a big, strong bugger,” Cocks said. “Dick came off at the third from the last. He had just gone to the front and was going to canter. Fortunately, the huntsman kept after him and caught him.”

Unhurt in his escapade, Zaccio started next in a maiden steeplechase at Fair Hill on May 12 and won by two lengths under McWade. “He always could run,” Cocks said. “I decided then to give him a little time off.”

Zaccio came back at Saratoga, where the money was good. Cocks put him into a $10,000 allowance on August 10, and the young gelding showed how much he enjoyed the game. Restrained by Skiffington for the first circuit of Saratoga’s inner turf course, Zaccio surged into contention on the backstretch and ran down Running Comment on the final turn. With Skiffington easing him, he hit the wire 9 1/4 lengths in front of Running Comment.

In an $11,000 allowance race on August 24, he was beaten a neck by Cocks-trained Parson’s Waiting, a homebred of Cortwright Wetherill who went off at 9-to-1. Zaccio, who was odds-on and ridden by Skiffington, bobbled after the last fence but was shaving his stablemate’s margin at the wire. “They thought we had split it and pulled him to let Parson’s Waiting win. But we didn’t. That was some race,” Cocks said.

Zac would not be beaten again as a three-year-old. He won an allowance at Belmont on October 11 and concluded the year with a 21-length victory at the Colonial Cup in Camden. It would be the final career victory for Skiffington, who went out as the champion jockey and launched his training career. But it was only the beginning for Zaccio and his championship seasons, who ended his maiden year with six victories from nine starts.

McWade was in the saddle for his first start at Aiken, South Carolina on March 22, 1980, and Zaccio carried 149 pounds to a five-length victory in the $7,500 handicap. A week later and with three additional pounds, he won the Carolina Cup by six lengths. He finished third in the Sandhills Cup at Southern Pines, beaten a length, and he came back with a less than convincing victory over Daddy Dumpling in Lexington’s Pillar Stakes on April 27.

At the end of May, Cocks tried Kentucky racing again, at the Hard Scuffle Steeplechase near Louisville, and 1979 steeplechase champion Martie’s Anger defeated Zaccio by 1 1/4 lengths. McWade had been close to the lead early but dropped back somewhat and could not catch Sheppard-trained Martie’s Anger through the stretch. “That’s when I got so mad at McWade. He was laying up and then fell back to fourth,” Cocks said.

He and Zaccio then went after the main tracks through the summer. The gelding won Monmouth Park’s Midsummer Steeplechase Handicap by three lengths, and this time McWade did not drop back. Zaccio was close up and then went to the lead over the eighth of 12 fences. They were on the lead throughout in Delaware Park’s Indian River Steeplechase Stakes on July 17, which Zaccio won by 4 1/2 lengths.

Then, it was on to Saratoga, where Zaccio won an epic battle with Martie’s Anger in the $43,875 Lovely Night Steeplechase. Under McWade, Zaccio drew away from Martie’s Anger in the stretch to win by 1 3/4 lengths.

Zaccio probably sealed his first title with a gutty performance in the New York Turf Writers on August 14. He and McWade took command early, but Running Comment ran by them at the last fence and opened two lengths. But Zaccio dug in through the stretch to win by 1 1/4 lengths. His time for the 2 3/8 miles was 4:14 1/5, trimming more than three seconds off the course record.

McWade suffered an extremely bad leg fracture at Foxfield in September, so Cocks turned to Doug Small Jr., his son-in-law at the time, to ride Zaccio in the Temple Gwathmey. It was a rough trip for the gelding. He was bothered at the eighth fence and unseated Small when he landed badly after the 11th. He was found to have fractured sesamoids in his right hind leg and underwent surgery to remove chips. His season was over, but he was the unanimous choice for the Eclipse Award.

Zaccio recovered from his injury, but during his recuperation he shifted his weight onto his forelegs and caused damage that would ultimately affect his soundness. Cocks gave him plenty of time, and Zaccio did not make his first start as a five-year-old until August 14, 1981 at Saratoga, when he ran ninth in a turf race. A week later, though, he came back in a handicap in which Codicioso (Chi) defeated him by 4 1/2 lengths in course-record time for the 2 1/16-mile steeplechase.

Always a good citizen when opportunities arose to promote steeplechasing, Cocks then shipped Zaccio to Chicago in late August to participate in the activities leading up to the first Arlington Million Stakes (G1). The trip proved to be disastrous; Zaccio was distanced. “He got sick shipping out there, and he came out of there with a fever,” Cocks said.

American Grand National at Foxfield. ©Lees

The trainer ran his star gelding in a Meadowlands Racetrack turf race to tighten him for the American Grand National Handicap at Foxfield in mid-October. With the ground rock hard, only Zaccio and Sailor’s Clue were entered to run, and Zac overcame a near fall at the seventh fence and prevailed by a diminishing neck. Aboard Zaccio for this trip was John Cushman, the son of Charlie Cushman and the first-call jockey for Sheppard.

Zaccio threw in another clinker in the Samuel K. Martin Steeplechase Handicap Cup at Far Hills, the home course of the Murdocks, on October 31. The course was rated as yielding, but the gelding went out quickly under Gregg Morris and was finished after 1 1/2 miles.

But the real Zaccio was about to make his reappearance. A week after the New Jersey fiasco, Cocks wheeled him back in the Noel Laing at Montpelier. After a few fences, Zaccio carried the battle to front-running Cookie and quickly ate him up. Zac was in front by 10 lengths at the eighth fence and by 15 at the wire.

His performance in the Colonial Cup on November 22 was even more impressive and sealed his ascendancy for a second straight year. Morris kept him in touch with the field for most of the race before taking him outside at the 15th of 17 fences. Zaccio gained the lead from Al Arof just before the last fence and cruised to an 11-length victory.

In 1982, Cocks sent Zaccio over fences seven times, and Mrs. Murdock’s gelding hit the board every time. The year began with some question marks, though, after Zaccio finished second to lightly regarded Quiet Bay in the Carolina Cup and last of three in the Delta Air Lines Atlanta Cup Steeplechase Handicap. After the Georgia race, Zaccio was found to have quarter cracks in the hoof of his left foreleg. Given some time, he returned in early July with an undistinguished effort in a turf race for steeplechase horses at Belmont. He went over fences again at Saratoga in the Lovely Night and was beaten by Quiet Bay.

But he would not lose again that year. Ten days after the Lovely Night, he crushed an excellent field by 16 lengths in a Saratoga handicap under Morris. Zaccio was entered in the New York Turf Writers on August 26, but he lost the services of Morris earlier in the afternoon when the rider broke his arm in a fall. Cocks then gave a leg up to his new rider, Ricky Hendriks. Zaccio opened a length at the last fence and held on to win by a length as Give a Whirl came back in the stretch.

Hendriks rode him to a flat victory at Fair Hill before his overpowering victory in that year’s Temple Gwathmey. Cocks then gave him another grass race, an eighth-place finish at Laurel Race Course, before shipping to South Carolina to defend the Colonial Cup. Again, Zaccio went by the field with a rush and won by eight lengths under Hendriks.

Cocks, who had two other winners on the card, rates that Colonial Cup as the most satisfying victory of his career. “It was one of the races we were looking forward to, and he had had some problems by that time, but it was really a kick to have him run the way he did,” the trainer said.

1982 Colonial Cup trophy presentation. ©Chronicle Independent